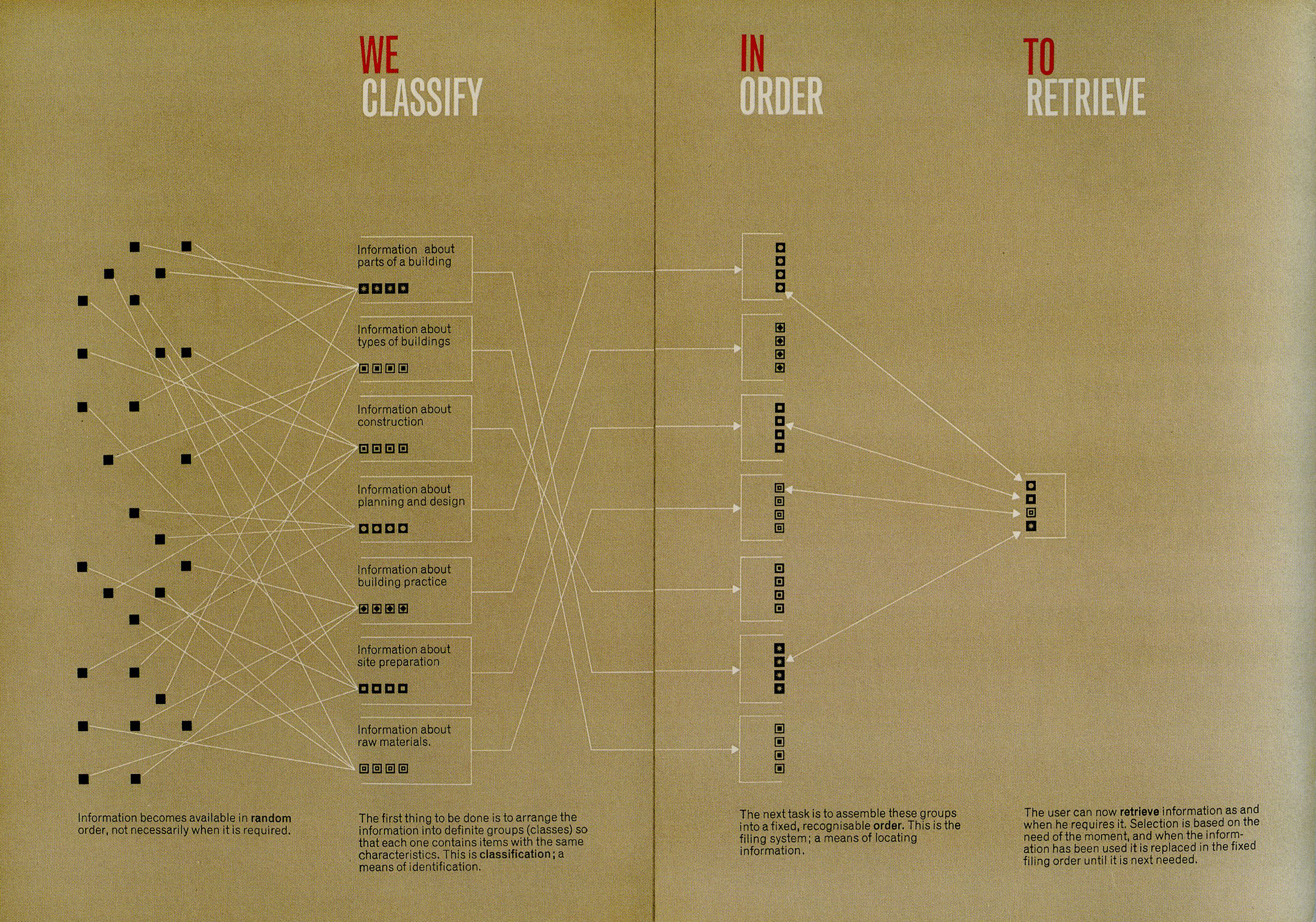

Process diagram for The Barbour Index, designed by Ken Garland, 1962. Design process (and some artistic practice) involves stages of research, an established archive, a systemized activation of it, and the refinement of multiple possible final narrative coherences, or ‘use value.’

Art and design, at best, act as inquiry: we can inhabit varied knowledge domains—all areas of the sciences and humanities—to gain a new sense of context for what may be speculative work, powered by research, and inflected with (even extended by) interpretive points of view. Art and design are natural companions for provoking speculation. Both can effect positive change, of both mind and matter.

In my own teaching, I argue for design’s essential task to cut a narrative path through data—that information is not (yet) knowledge. A design process begins with a search (which may originate in an archive as database), coalesces into research, assembles an archive of findings, employs systems to organize and activate the archive, extends/actuates the systems into a network of associations and processes, and shapes this process into focused narrative coherence.

In her recent RISD lecture, Information Overload: Research-based Art and the Politics of Attention, Claire Bishop talked about the need for ‘critical synthesis’ when using research within a visual practice; she cited reluctance to edit as a symptom of research-based art. Research tempts us to accumulate, assemble, and display in a way that demands ‘spectatorial labor’ to view its distributed mass within vitrines, in panels, on tabletops. As Bishop says, ‘Quantity removes mastery.’

One could continue to exhaustively amass research material: one thing leads to another. But to simply try to show it all is exhausting, both for maker and viewer. When, and how, does research end, and critical synthesis begin as new (transformed) visual, verbal, spatial, experiential, and interactive form?

Bishop argues for a ‘post-hermeunetics’ of artistic practice—open-ended, networked, and rhizomatic. She calls for art to place pressure on other disciplines (she mentioned psychotherapy as example; also technologies, sciences, politics, etc.), citing the Center for Land Use Interpretation as a model for artistic practice: a collaborative distributed model of a website database, a set of talks, tours, performance, and exhibitions. Using links as a dominant mode, this kind of practice becomes a map of connections, also allowing for digression, extension, and speculation.

From ‘Art Cannot Provide a Way Out,’ Ryan Wong’s Hyperallergic review of Bishop’s book:

To be reductive for a moment: if a project is about hunger, by the ethical standard it is judged on how many it feeds rather than the questions it raises about feeding. In Bishop’s view, participation is nothing less than a quest to escape the “alienation induced by the dominant

ideological order—be this consumer capitalism, totalitarian socialism or military dictatorship.” Art cannot (and, in Bishop’s opinion, should not try to) provide a way out. But it can shock, enrage and maybe even delight us into new possibilities, artificial though they are.

The 1939 World’s Fair archive offers aesthetic and political inspiration in its many designed forms: diagram, map, site, pavilion, text, color, material substance, spectacle, event, participation, publication, broadcast, etc. Subsequent stages of this project will experiment with, and explore within, these forms in ‘a quest to escape the alienation induced by the dominant ideological order...’.