3. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) (1)

Educational exhibits of The New Deal government programs focused on social welfare to contrast the crass commercialism of the Fair. Planners, designers, writers, performers, and artists used their skills to emphasize the New Deal agencies’ key concepts of self empowerment and community engagement for the public good. Narrative displays depicted systems and processes that argued for the government’s role in housing, healthcare, and labor.

The WPA’s pavilion featured displays of the many Agency’s projects.(2)

(below) Displays for the Department of Labor and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA).

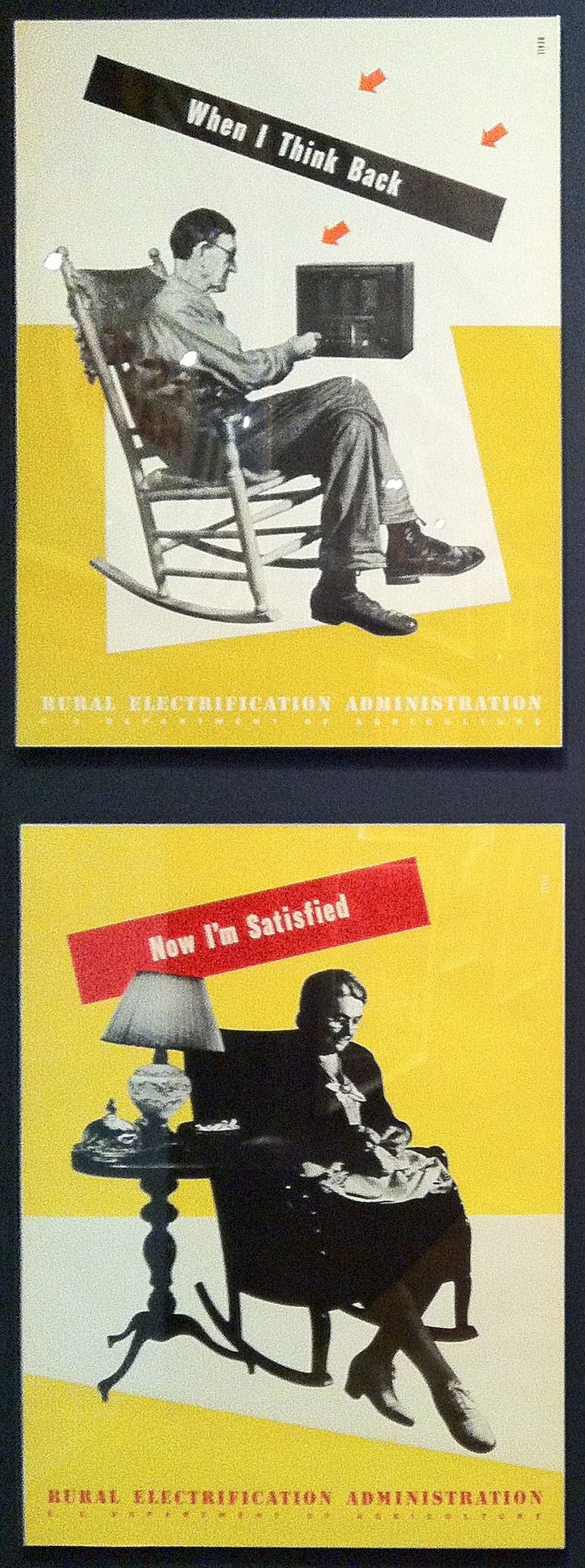

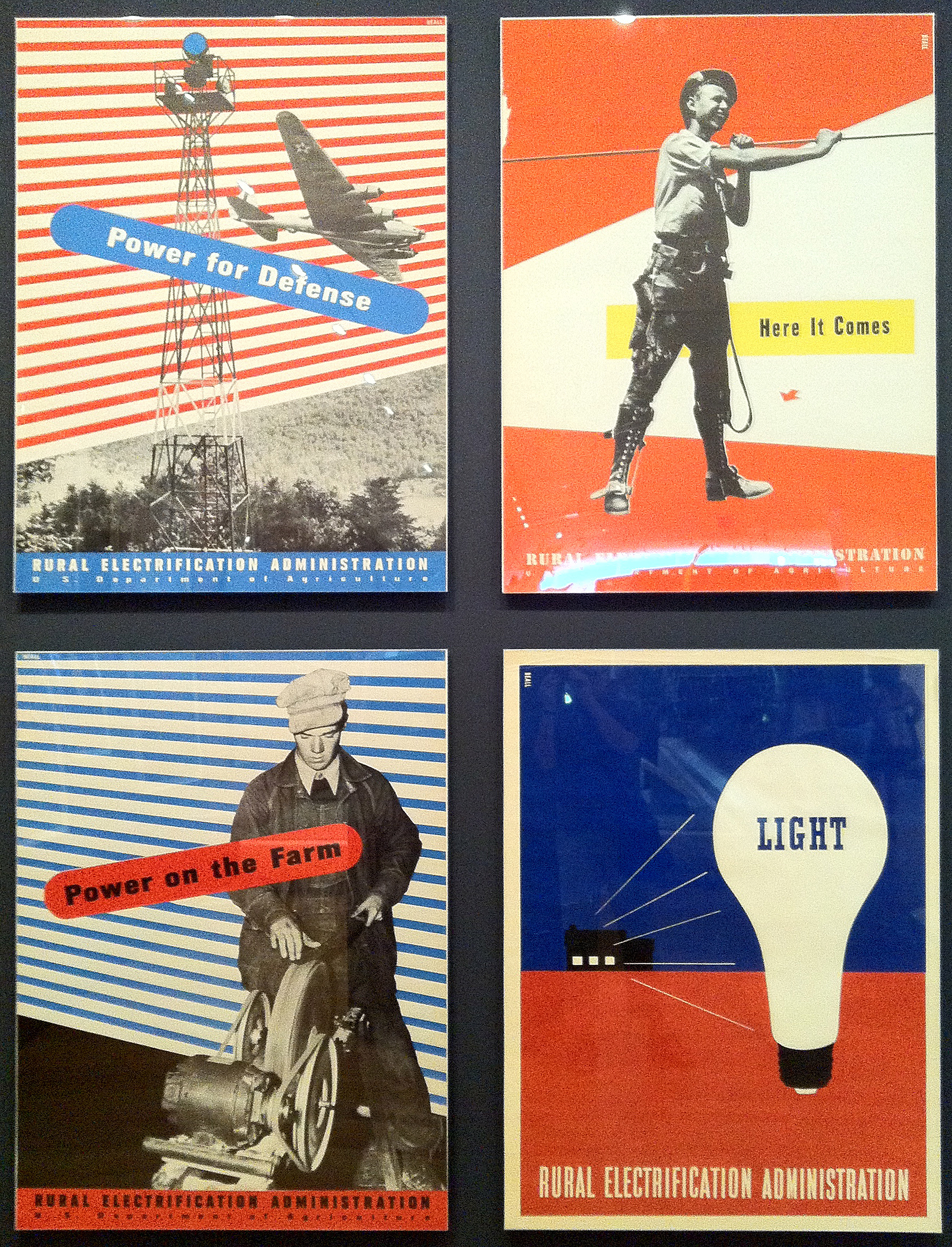

In the impoverished rural areas of the mid-1930s as few as ten percent of homes had electric power. The WPA’s Rural Electrification Administration distributed posters designed by Lester Beall (3) to post offices across agricultural areas to promote the coming upgrade to an electrical power network. Design historians have noted the simplified poster text as a likely consideration of the limited reading skills of the rural poor.

Beall also had other Fair commissions: For the 1939 Fair, Beall was commissioned to create a poster for The Freedom Pavilion, a structure that was to house presentations about Germany, until Hitler’s aggression in Europe on the eve of the Second World War led to the project’s demise. (Published in Eye no. 24 vol. 6, 1997)

Teaching Tolerance

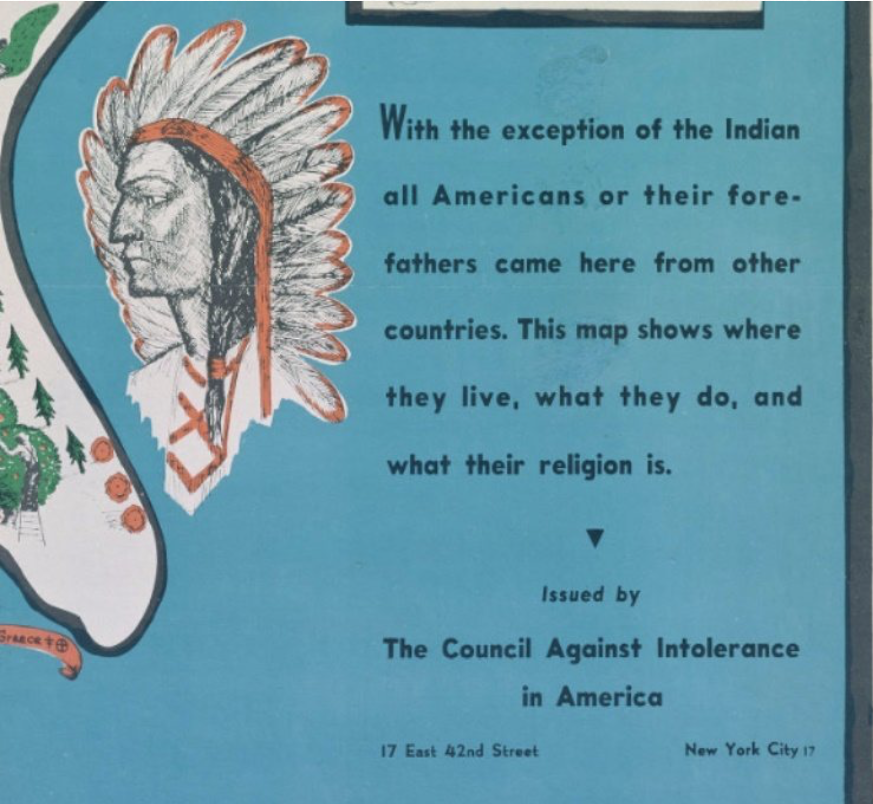

The Council Against Intolerance in America was a New York City-based group that was active from the late 1930s to the mid-1940s. The group's mission was to promote racial and religious tolerance through education, and its materials argued that prejudice would undermine national unity during wartime. The Council was led by James Waterman Wise, a Jewish author, art dealer, and lecturer who had warned of the dangers of Nazism in books as early as 1933.

![]()

The council distributed teacher’s manuals, postage stamps, and publications such as The Negro in American Life, The Jew in America, Calling All Americans: A Handbook of National Unity, and—to counter Charles Lindbergh’s pre-War pro-Nazi speeches— America Answers Lindbergh!

The council distributed teacher’s manuals, postage stamps, and publications such as The Negro in American Life, The Jew in America, Calling All Americans: A Handbook of National Unity, and—to counter Charles Lindbergh’s pre-War pro-Nazi speeches— America Answers Lindbergh!

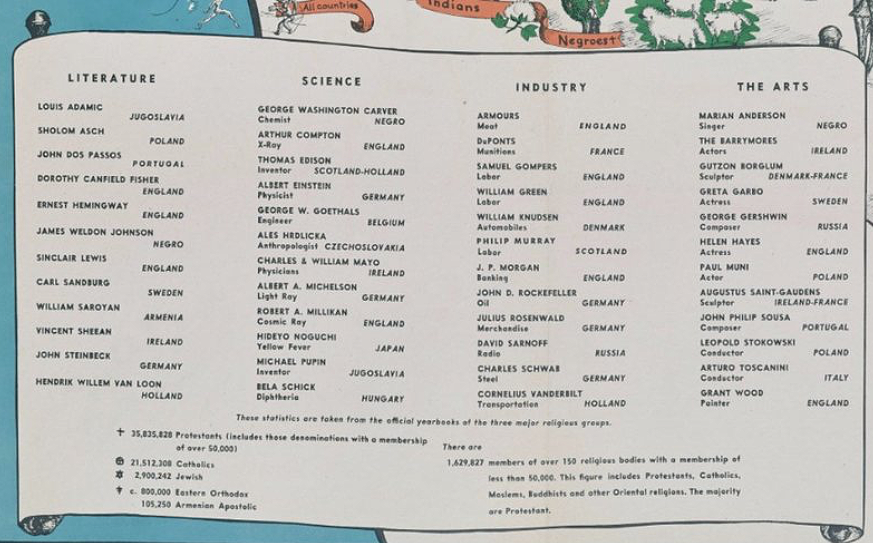

From the late 30s to the mid 40s, The Council Against Intolerance in America’s educational department distributed information and material designed to strengthen the ‘basic American principles of mutual tolerance and equality.’ This map, America—A Nation of One People From Many Countries, was illustrated by African-American printmaker Emma Bourne. Published in 1940, it portrays America as a nation of immigrants (reportedly, however, poet Langston Hughes annotated his copy with a drawing of a burning cross and references to the KKK near the area showing cotton workers in the South). Unfortunately, very little information can be found on Emma Bourne’s (4) biographical details and her involvement with the WPA:

“The Works Progress Administration (WPA) hired artists for the Federal Art Project, or FAP, (5) as one branch of their efforts to combat unemployment. The group of artists who were part of the FAP worked on research, education, and production of art in many different media such as painting, sculpture, photography and the graphic arts. Through WPA funding, artists gained access to expensive materials, which made printmaking (generally an equipment-heavy and community-based medium) a possibility even for the underprivileged. ...

The FAP created funds for artists, musicians, writers and actors in various art projects across the country. This project was a part of the New Deal because much of the administration responsible for its creation believed that art should be a part of everyone’s life, not just for the elite class in order to enrich and embolden people. While the main objective was to combat unemployment, the group of artists who were part of the FAP did research and educated school children as well as produced art in many different media such as painting, sculpture, photography and the graphic arts. There were several popular graphic arts workshops in large cities such as Philadelphia and New York, where Black families would send their children to receive art instruction.”

Map details of the Council Against Intolerance in America’s America—One Nation of Many Peoples by African-American illustrator, Emma Bourne, 1940.

America remains splintered into regions and tribes with persistent patterns: see The Maps That Show That City vs. Country Is Not Our Political Fault Line.(6) “The key difference is among regional cultures tracing back to the nation’s colonization.”

America remains splintered into regions and tribes with persistent patterns: see The Maps That Show That City vs. Country Is Not Our Political Fault Line.(6) “The key difference is among regional cultures tracing back to the nation’s colonization.”

Our national id continues to be vexed by intolerance of every kind. A persistent challenge with immigration persists, met with raids, threats of a wall between the U.S. and Mexico, and detention of illegal immigrants. The current administration is even considering revoking (7) the citizenship of landed, documented, naturalized immigrants: It has organized a Citizenship and Immigration Services task force to denaturalize American citizens, the first effort of mass expatriation contemplated since the McCarthy era. (NYT)

Immigration (8) debates and conflicts continue to dominate the globe as populations are displaced by genocide, war, and dramatic climate events.

Alternative Contexts: Social Realism and the WPA

The Federal Art Project (9) within President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided many struggling artists with patronage, a sense of community, and the mandate to paint realistically. Within the 1930s historical context, a very large and diverse group of artists later called the Social Realists joined together to publish magazines, organize unions, convene artists’ congresses, and publicly agitate for the importance of their revolutionary work, the role of the artist within society, and radical anti-capitalistic change for America. Social Realists (10) who considered themselves to be workers established their own labor union called the Artists’ Union. The Artists’ Union was an affiliate of the dominant labor union of the time, the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Members of the Artists’ Union agitated for permanent federal art programs and better wages for artists under the New Deal. The American Artists Congress convened in 1936 and Social Realists were among the hundreds in attendance.”

The 1939 Fair featured sculptures and murals, many of which were crafted by WPA artists who were likely grateful for the work despite its support for the capitalist powers they resisted. With work in every medium, the Social Realists cast critical shadow on the industries of war using the very materials the Fair promoted.

The Architectural Forum ad for World’s Fair vendor General Bronze Corporation contrasts with sculptor David Smith’s 1939 Medals for Dishonor, cast bronze works with accompanying text decrying fascism and those complicit with war production.

“The American Artists Congress convened in 1936 and Social Realists were among the hundreds in attendance. This was part of the Popular Front’s attack against global fascism with the rise of Adolf Hitler and, even locally, with Father Charles Coughlin (11) stirring anti-Semitic sentiments. In addition, artistic censorship was on the mind of many with Nelson Rockefeller’s infamous cancelations of Diego Rivera’s mural in Rockefeller Center (1933) and Ben Shahn’s mural for Riker’s Island Penitentiary (1934). Pressing social events of the day held sway rather than aesthetic debates.”

The art of the 1930s leading to the 1939 World’s Fair depicted the tense social and political conditions of the times. Ben Shahn, Demonstration, 1933 (detail), Harvard Museum.

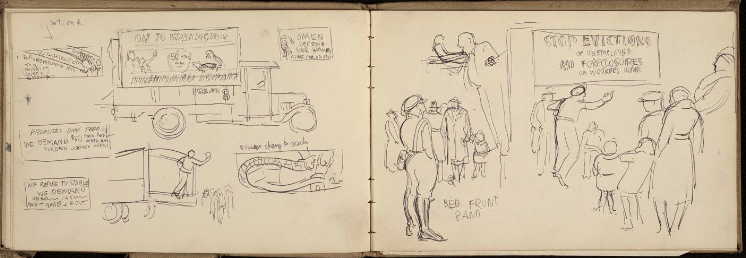

(below) Lewis W. Rubenstein and Rico Lebrun, The Hunger March, 1933 (fresco details), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum. Lewis W. Rubenstein sketchbook studies (12) for the Hunger March fresco mural, 1933, Harvard Museum.

World’s Fair murals were idealized and stylized figurative depictons of narrative themes. Rockwell Kent (13) was one of the commissioned artists for the Fair’s large scale murals, shown in his studio at work on his mural for G.E. (detail below). “Throughout his life, he supported left-wing causes and was a member or officer of many organizations promoting world peace and harmonious relations with the Soviet Union, civil rights, civil liberties, antifascism, and organized labor.”

(below) Artists delivering submissions to be considered for inclusion in various Fair exhibitions; juries selecting work for display.

The Fair’s IBM building featured an exhibition with performance and radio programming for A Salute To The Arts, wth a broadcast that included the music of Erik Satie, Igor Stravinsky, and John Cage, and commentary by Merce Cunninham, representing the Black Mountain School.

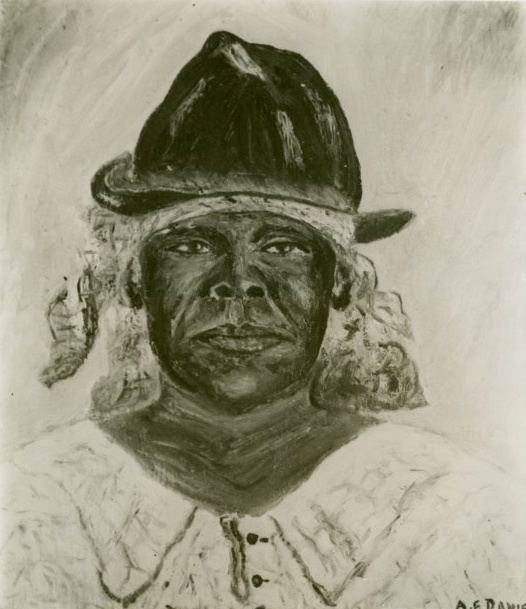

The art on display depicted ‘peoples of all nations’ as well as more abstract pieces that hint at the social strife of the Great Depression, as well as the devastations of the Dust Bowl affecting much of the nation.

Clockwise: portraits representing Honduras, Hati, Virgin Islands, and Jamaica.

(below) Dramatic depictions of the effects of the Dust Bowl.

Notes/links:

(1) The Works Progress Administration, Britannica; (2) The New Deal Agencies, livingnewdeal.org; (3) Design Pioneers: Lester Beall, Bill Starkey, Research Commons at Kutztown University; (4) Emma Bourne, American artist (very little information is available on her life and work); (5) Federal Art Project, with list of participating artists [Wikipedia]; (6) The Maps That Show That City vs. Country Is Not Our Political Fault Line, Colin Woodard, NYT; (7) Trump’s New Target in the Politics of Fear: Citizenship, NYT; (8) Migrants Are on the Rise Around the World, and Myths About Them Are Shaping Attitudes, Eduardo Porter and Karl Russell, NYT; (9) Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration, theartstory.com; (10) Social Realism (many of the artists who participated in the creating the Fair’s murals were considered Social Realists), theartstory.com; (11) Charles E. Coughlin, facts from the American Holocaust Memorial Museum website; (12) Sketchbook documenting a hunger march to Washington D.C., Lewis W. Rubenstein Papers, 1923–93, Smithsonian; (13) Rockwell Kent Papers, biographical note, Smithsonian; (14)