Printing press demonstration at the 1939–40 World’s Fair

There are many ways to read, curate, configure, juxtapose, cluster thematically, construct arguments, assay predictions, provide chronology, and reveal hidden or forgotten networks of meaning from assembled research. Moving from archive to action is the challenge: the problem is that it’s difficult to stop gathering, and start making sense of the assembled data.

What is the story? What is the point? Is there one, or many?

Kate Crawford describes the paradox of overwhelming uncertainty in the midst of an archive’s evidentiary and factual material in her essay “Asking the Oracle” published in the exhibition catalogue for Laura Poitras’s Whitney Museum exhibition, Astro Noise. Crawford refers to her immersion in Snowden’s NSA archive, but the same holds true for any archival research:

Know Thyself

The archive is the ultimate rabbit hole. Days can pass without stopping, without eating: I barely rise from the desk. It feels like I can see into the complete structure of a global system, spread out before me in neat network diagrams. This, of course, is an illusion. The archive is always partial—necessarily incomplete... There are blank spaces, dead ends, and missing parts.

(from Laura Poitras—Astro Noise: A Survival Guide, p. 143)

The archive is the ultimate rabbit hole. Days can pass without stopping, without eating: I barely rise from the desk. It feels like I can see into the complete structure of a global system, spread out before me in neat network diagrams. This, of course, is an illusion. The archive is always partial—necessarily incomplete... There are blank spaces, dead ends, and missing parts.

(from Laura Poitras—Astro Noise: A Survival Guide, p. 143)

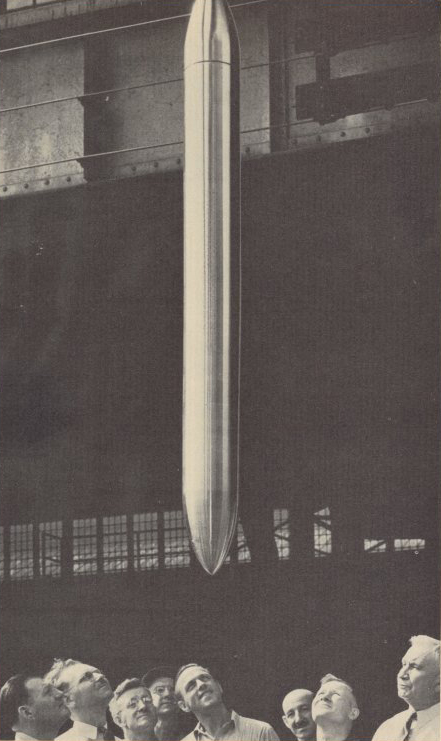

(Right and below) Contents, assembly, and burial ceremony of the Westinghouse Time Capsule, meant to capture key elements of the cultural and material life of 1939: “deemed capable of resisting the effects of time for five thousand years, preserving an account of universal achievements, embedded in the grounds of the New York World’s Fair, 1939.”

This research project is itself a kind of time capsule as 1939 and 2019 align: what can survive this interest in the 1939 World’s Fair, and what does it want to be? The Fair provides a case study of America’s state(s) of being then and now relative to visual spectacle, material culture, art and design, big business, our own history, a world of perpetual war, the ideals of democracy, and the notion of ‘futuring’. All fields are active and dynamic.

A turn to the political is inevitable when evaluating the echoes of the Fair within the world of today: we are reliving similar struggles between social justice and welfare (i.e, the WPA) and the borderless and boundless drives of neoliberal capitalism (i.e., Bernays, Arens).

To some degree, any creative work necessarily operates in a world of seemingly endless conflict—social, cultural, political, military, and environmental. An enmeshed global network offers progress while simultaneously eroding civic structures both physical and philosophical. When art and design ‘is political,’ it is turning a critical lens on (and making visible) sociopolitical constructs, global systems and networks, and contemporary technological conditions. We can reveal and try to make visual/verbal spatial/experiential sense of power structures and cultural forces—of institutional and corporate structures, market economies, public policy, social media and information proliferation, race and nationality, insidious surveillant technologies, the reaches of empire, the economies and technologies of war (...Art cannot provide a way out. But it can shock, enrage and maybe even delight us into new possibilities, artificial though they are [Claire Bishop]).

I’ve titled this Shadow Fair: The Unfinished Business of the World of Tomorrow; doubtless there are huge and depressing contours to the shadows now that Tomorrow is here, and a lot of unfinished business. The films of Adam Curtis and the work of Poitras and many others examine that aspect exquisitely, if darkly.

Conspiritorial thinking is a hazard with this material, at least based on how many pieces of the 1939 story link American business with war profit, eugenics, Nazism, and the other ‘indelible shadows’ of Part 2. This history could lead us inexorably to imagine endless world war, or any number of variations on an apocolyptic future—one to parallel (even exceed) what could be reasonably presupposed based on the state of the world in 1939 and what ultimately came to pass. Conversely, and with cautious optimism, America may be on the cusp of awakening to a new progressive era for which the New Deal and WPA offer intruiging models for policy and culture to join forces.

Construction photo from NYPL Fair archive.