The 1939–40 World’s Fair was in its way a modest model for ‘soft power’ nation-branding (1) that would be perfected in subsequent World’s Fairs and Expos (the 1964 New York World’s Fair would take place on the same fairgound site at the height of the Cold War era). It’s likely that the 1939 Fair advertised America chiefly to itself, with a very small percentage of international visitors. Few Americans travelled abroad in the 1930s, and prior to the development of an interstate system (itself a result of the 1939–40 World’s Fair’s futuristic designs) many rarely travelled far from home. Americans likely made the Fair in New York City an exotic destination in itself. The ‘World’ in the 1939–40 World’s Fair was dominated by American representations of its own material and cultural achievement; the pageantry and performance of international customs and cultures were designed for the relatively isolated American audience.

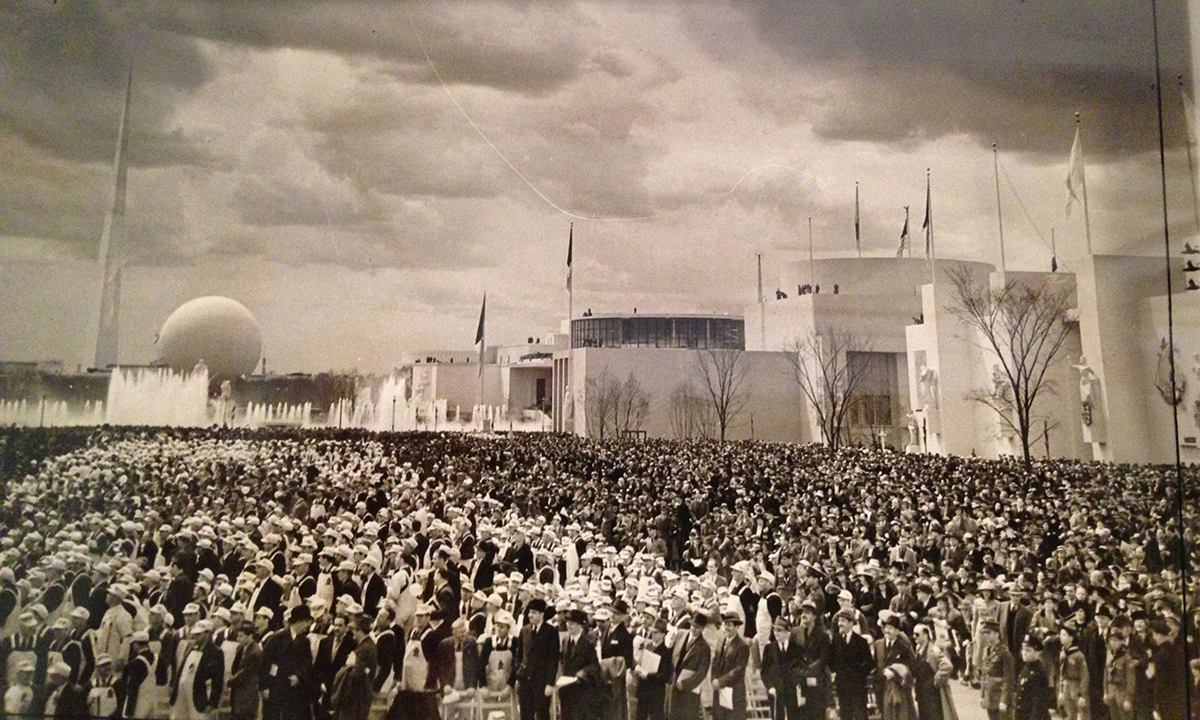

(above) Rendering for the transportation arrival area from the Board of Design; opening day at the Fair.

(above) Rendering for the transportation arrival area from the Board of Design; opening day at the Fair.The Fair essentially served to portray America as a strong leader, shaking off the effects of the Great Depression and emerging to demand a world stage. With Democracy and Progress as its guiding themes, The Fair would maximize its image as a competitor for world trade and business. The themes would be demonstrated through spectacle and visual display as a kind of ‘proof of concept.’

Much has been written about international expositions as agents of soft power—a persuasive form of international cultural statecraft—and the role of design in the history of the USIO (United States Information Agency) is beautifully illustrated in the book Cold War Confrontations: US Exhibitions and Their Role in the Cultural Cold War (2) by Jack Masey and Conway Lloyd Morgan (Lars Müller Publishers). A current State Department entity, Public Diplomacy Association of America (3) (a newer incarnation of the USIO) is developing a 2020 Dubai Expo, with promotional text reminiscent of the 1939–40 World’s Fair:

“Expos are considered a cost-effective platform to promote commercial and public diplomacy objectives, reaching millions of people in-person and millions more through traditional and social media. ...The theme of Expo 2020 Dubai is “Connecting Minds, Creating the Future,” representing the potential of what can be achieved when meaningful collaborations and partnerships are forged. The Expo’s subthemes are Opportunity, Mobility, and Sustainability. The USA Pavilion will emphasize the “Mobility” sub-theme, and the pavilion’s architecture and interior design will communicate American progress, ingenuity, and innovation in social, physical, and mechanical mobility in commerce and the arts.”

Uncle Sam as American symbol became more prominent as the Fair entered its second year in 1940, with the U.S. entry into the war.

Edward Bernays, the ‘Father of Public Relations’

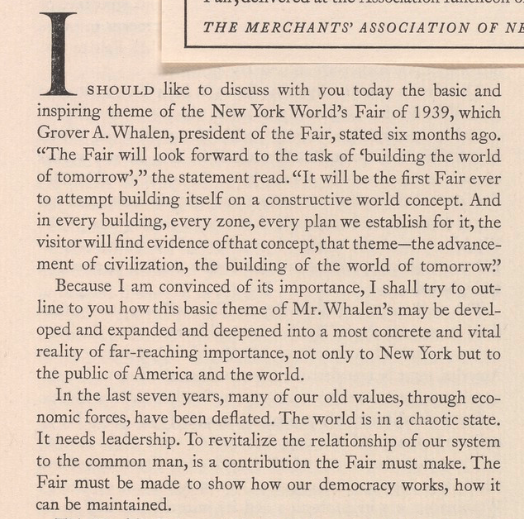

Public relations master Edward Bernays (4) provided the persuasive rationale for the Fair as A Symbol of Democracy in his address to the prospective merchants whose buy-in was needed to make the Fair a success.

From excerpts of Bernays’ address to the Merchant’s Association of New York:

The millions who will visit your Fair will see our institutions in concrete forms. But beyond and beneath that, the institutions—industrial, economic, social, and political—that have made America must be translated into new values, showing their relationsip to the American system—to our freedom and our liberty. ‘Let us sell America to the Americans.'

Bernays knew he was speaking to a nation pulling itself out of The Great Depression and striving to scaffold a prosperous future: “It will be the first Fair ever to attept building itself on a constructive world concept.”

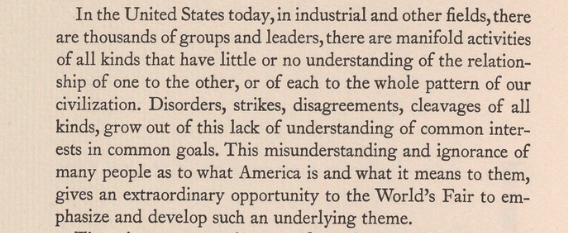

He claims that Americans are ignorant of what America really means to them: “...there are thousands of groups and leaders, there are manifold activities of all kinds that have no understanding of the relationship of one to the other, or of each to the pattern of our civilization...”

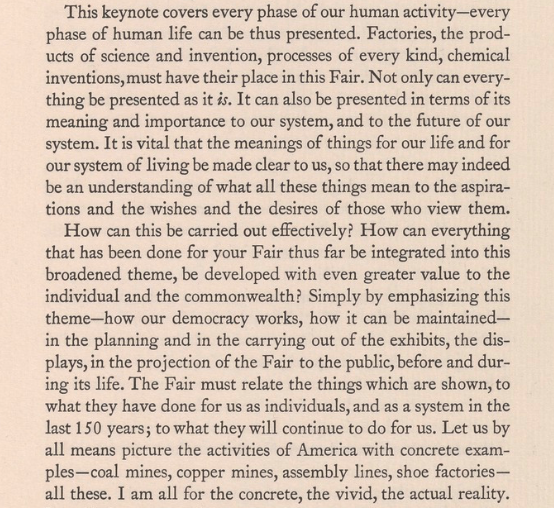

He exhorted all merchandizers and manufacturers to bring their goods, services, and messages into full view at the Fair: “..Let us by all means picture the activities of America with concrete examples— ... I am all for the concrete, the vivid, the actual reality.”

Man AND the Community vs. Man IN the Community seems to argue that complex interdependence—especially with ‘public services’ such as Education and Health taken care of by government policy—allows for more leisure time. It follows that more leisure time would encourage more consumer activity, travel, and recreation.

Selling America: Spectacle and Seduction

For all of the care Bernays and Fair designers gave to developing the Fair’s lofty themes and goals, the chief task of Fair organizers was to get ordinary Americans to attend the Fair in the first place. All manner of advertising and incentive was devised to entice visitors, and to entertain them once they visited. Bernays, in his Democracity address to merchandisers, sees the Fair as an ‘extraordinary opportunity’ to enlighten Americans whose ‘misunderstanding and ignorance of what America is and means to them’ leads to disorder and a lack of common goals. Part of the Fair’s visual strategy involved orchestrating elaborate lighting, color, and water features to elicit awe and majesty equal to the Fair’s themes.

Once there, visitors could (ostensibly) learn from exhibits showing technological and material innovation; their tastes could be cultured and attuned to wanting more, and more modern, products as material evidence of American progress and democratic success. This World of Tomorrow was based on consumption and entertainment in all its forms; American values would be performed to appeal to all the senses. “Amusement” could be understood as a byproduct of the leisure time to be gained by the new products’ promise—to allow people to get more done—much faster, more efficiently, and in a distinctly modern style.

A huge proportion of the Fair, however, seemed to appeal to American’s basest instincts for diversion and amusement. The archive’s images reveal much of the entertainment at the Fair as the equivalent of a carnival sideshow or risqué burlesque performance. Daytime images of the Fair bely the magic of the nighttime artistry of light and color, showing corny temporary structures and diminishing the sense of scale to that of the carnival midway.

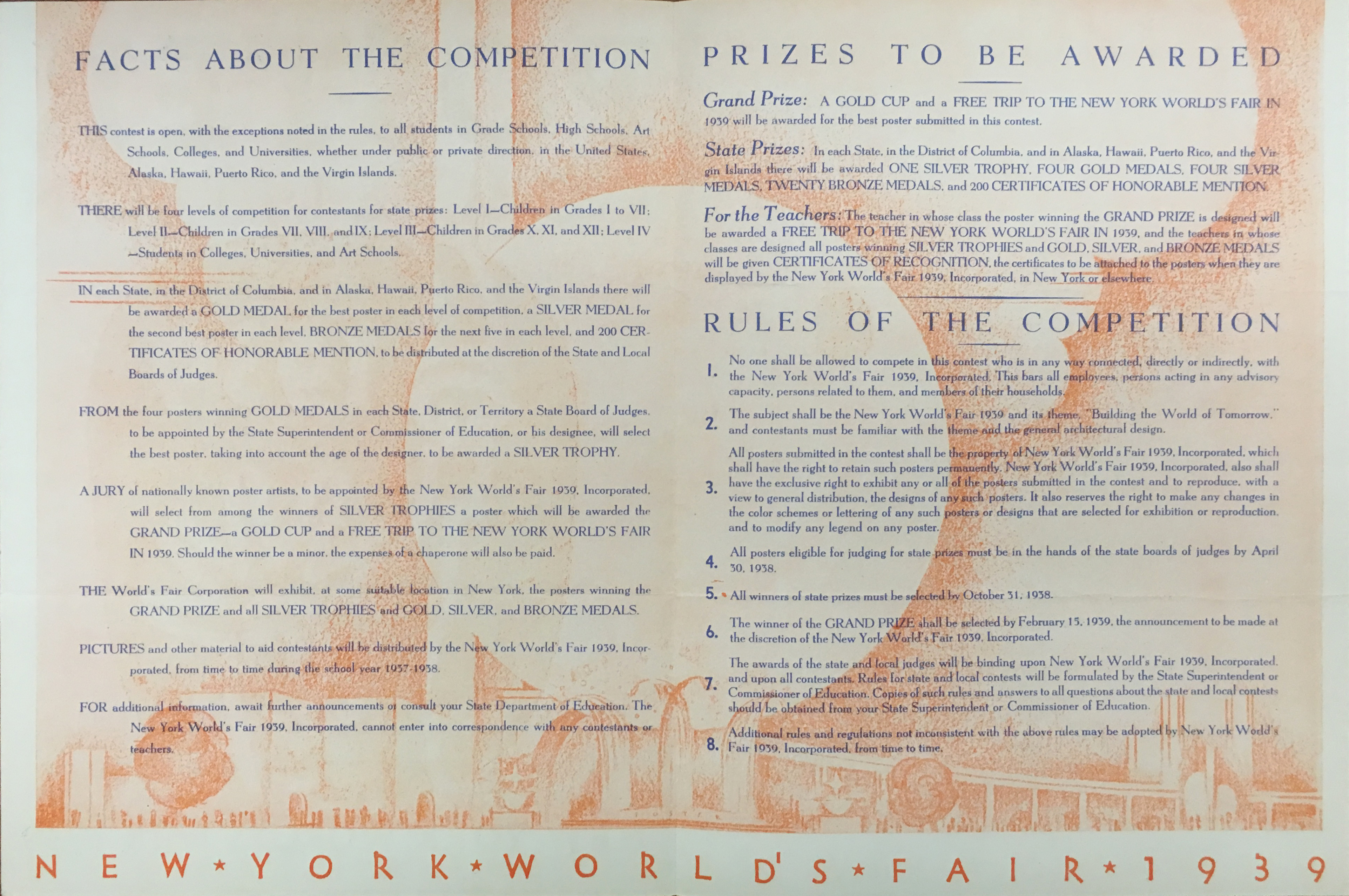

The Fair organizers relied on a carnival atmosphere to attract people to the events. Along with rides and sideshow attractions, contests were a device used to draw attendance.

A visit to Midget Town was one of the many contest prizes; observers watch a mock casting-off of Satan at the Temple of Religion; a Hitler-look-alike cat contest; participants in a Hayfever Sneezing Contest.

As the Fair entered into its second year (1940) The Typical American Family Contest invited a competition for families from ‘several trading areas of the United States’ to travel all-expenses-paid to the Fair, and to live there on the fairgrounds in ‘two small American homes [to] be built adjoining the Town of Tomorrow.’ (A State Fair version of this same kind of contest is interpreted by artist Zoe Beloff's in her film A Model Family in a Model Home,(5) part of her larger project, A World Redrawn.)

Ordinary Americans across the country could submit to poster and essay contests (this one’s theme: “Why I Want to Go to The World’s Fair”). Winners received free tickets to the many theme exhibits, shows, contests, and performances within the Amusements Zone.

Notes: (1) Public Interactives, soft power, and China’s future at the 2010 Shanghai Expo, Sage Journals blog; (2) Cold War Confrontations: US Exhibitions and Their Role in the Cultural Cold War, Jack Masey and Conway Lloyd Morgan, Lars Müller Publisher; (3) Public Diplomacy Association of America; (4) Edward Bernays, ‘the father of public relations’ [Wikipedia]; (5) Artist and filmmaker Zoe Beloff interprets history with archival and restaged material in A Model Family in a Model Home, part of her larger project, A World Redrawn (“A World Redrawn is an exploration by the artist Zoe Beloff of Sergei Eisenstein and Bertolt Brecht’s experiences in Hollywood in the 1930s and ‘40s, what their time in Hollywood meant to them then and what it might mean to us now. Beloff focuses on two unrealized films written during this time: “Glass House” by Eisenstein and “A Model Family” by Brecht.”—zoebeloff.com)