4. Material World

An ad for Time magazine’s potential advertisers characterizes Time readers as more conscious of how the news affects their prosperity (and more likely to respond to an ad for the Nash automobile).

Production and Persuasion

The Fair’s and the popular media’s patriotic messaging were public relations (1) efforts to shape an American sense of self, and its vision for the future. The 1939 World’s Fair was in its own way the test case for planned obsolescence—an economy based on want and consumption, not on need and product endurance. (See Adam Curtis’s Century of the Self, Part 1: The Happiness Machines (2) and the role of Edward Bernays in shaping the corporate messages of the 1939 Fair. Egmont Arens, arguably the father of planned obselescence, is discussed in Part 3.2.)

The world of tomorrow was primarily represented by merchandise—designed, produced, displayed, and distributed with no restraint and no borders. Products became a symbol for democracy.

The New York world’s fair, a symbol for democracy: (3) address of Edward L. Bernays, member of World’s Fair Committee of the Merchants’ Association of New York at luncheon under auspices of the Association’s Members’ Council at Hotel Pennsylvania / April 7, 1937 (excerpted from full pdf, Yale University Library / Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library)

Edward Bernays (4) worked with many of the corporations on their exhibits for the Fair to promote a vision of Democracy based on satisfying consumer needs as the truest form of patriotic duty. Plastics, automobiles, steel, and countless other industries were represented in elaborately designed display. A cast of design ‘heros’ were put to work: Donald Deskey, Norman Bel Geddes, Henry Dreyfuss, Egmont Arens, and many others (with women largely absent in the lists).

Excerpts from New York World’s Fair Licensed Merchandise, an extensive handbook for participating manufacturers, exhibit fabricators, and industry vendors.

The message of abundant resources, manufacturing might, and the flow of goods and services was situated at the core of the Fair’s mission—and has clear parallels in America today. The Fair provided the souvenir as a kind of totemic take-away for visitors—objects tha survive as material extensions of the Fair experience. There is an almost endless supply of printed ephemera that survives from the 1939–40 Fair; legions of collectors and enthusiasts (5) also collect World’s Fair glasses, silverware, Bakelite plastic, metalworks, pottery, textiles, and so on. While my interest in the Fair may have begun at the flea market, it is now focused less on object acquisition and more on understanding the role of the Fair in forming a national idea of identity and prosperity in light of troubling social realities of the time.

A chromatic display of 1939’s new plastics of the chemical company Monsanto (its later ‘House of the Future’ (6) was exhibited at Disneyland, 1957. Monsanto operated the Dayton Project, later Mound Laboratories, assisting in developing the first nuclear weapons. Monsanto went on to manufacture DDT and Agent Orange, and has merged with German chemical giant, Bayer, in genetically modified food research.)

General Motors brochure, and advertisements from Architectural Forum, June 1939. Today, cheaper labor forces, lower taxes, and looser environmental regulation have contributed to Americas manufacturing’s move offshore to effectively colonize other countries.

What legacies have endured from The 1939 World's Fair? The Fair was a mammoth design project that harnessed the imagination of graphic, industrial, exhibition, and architectural designers. Visions of the World of Tomorrow as spatial and distributive featured dynamic land use, transportation systems, and areas for community use. Pavilions, exhibits, and concept drawings rendered the future visible. From the Official Guide to the Fair:

The eyes of the Fair are on the future — not in the sense of peering toward the unknown nor attempting to foretell the events of tomorrow and the shape of things to come, but in the sense of presenting a new and clearer view of today in preparation for tomorrow; a view of the forces and ideas that prevail as well as the machines.

To its visitors the Fair will say: “Here are the materials, ideas, and forces at work in our world. These are the tools with which the World of Tomorrow must be made. They are all interesting and much effort has been expended to lay them before you in an interesting way. Familiarity with today is the best preparation for the future.

What is left of the actual material 1939–40 New York World’s Fair beyond its archive of business records and ephemera, documentary photos, home movies, myriad souvenirs, and fan base of collectors? Once its memory passed from generations,(7) how would it or could it preserve for posterity what it considered to be its greatest achievements?

The Westinghouse Time Capsule

The 1939–40 New York World’s Fair site plan featured thematic zones, buildings, pathways, and pavilions—occupying a single year and in spatially ephemeral scope on a reclaimed site, now the home of the Queens Museum of Art in the only building remaining from the sprawling 1939 Fair campus. The New York Public Library archive is now the permanent site of the 1939–40 Fair: an organized data environment of files, documents, photographs, diagrams, media, texts, architectural plans, and proposal renderings. But the aim of the planners at the time was to leave something for a future 5,000 years away, a proposition that fit with the Fair’s many spectacles.

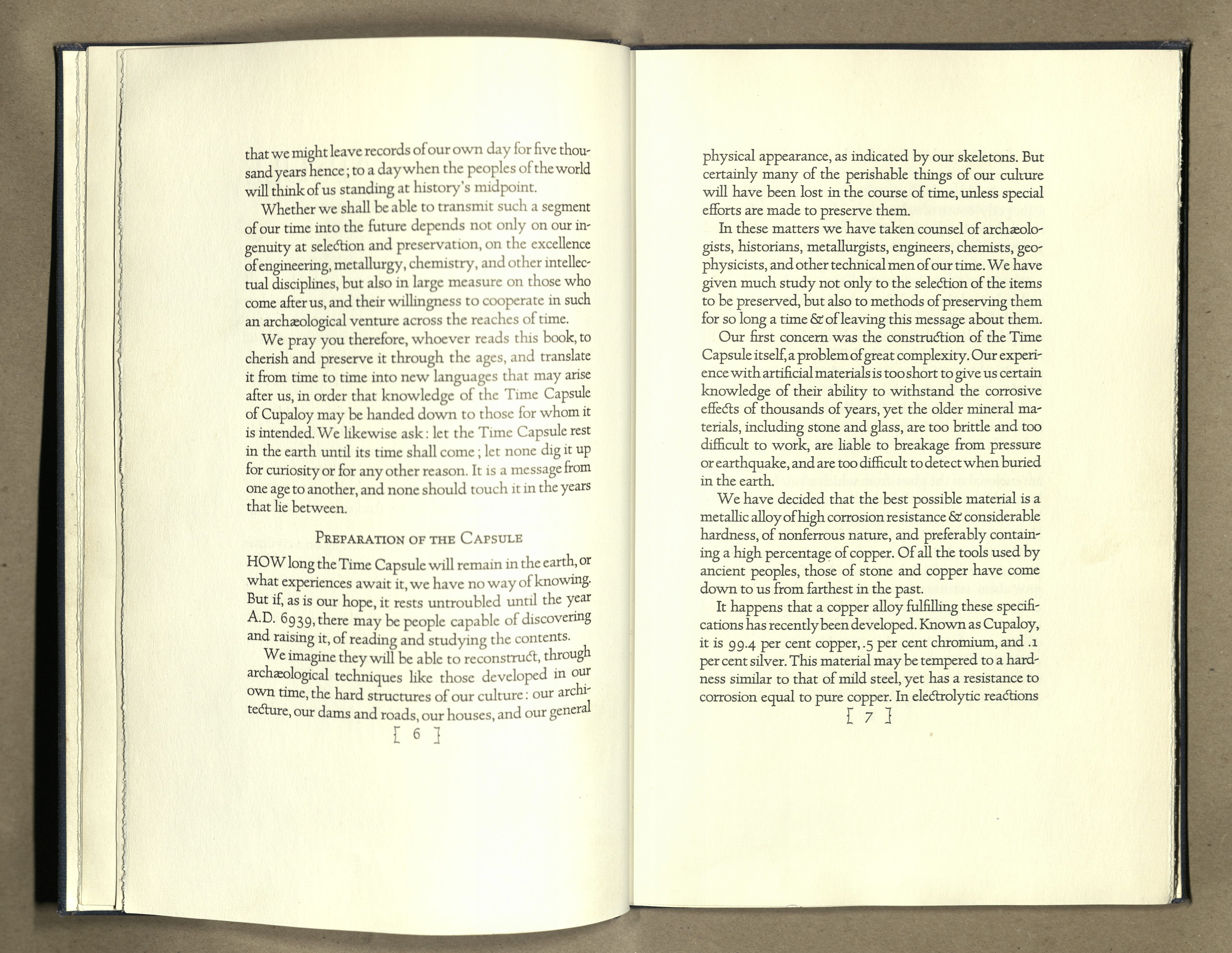

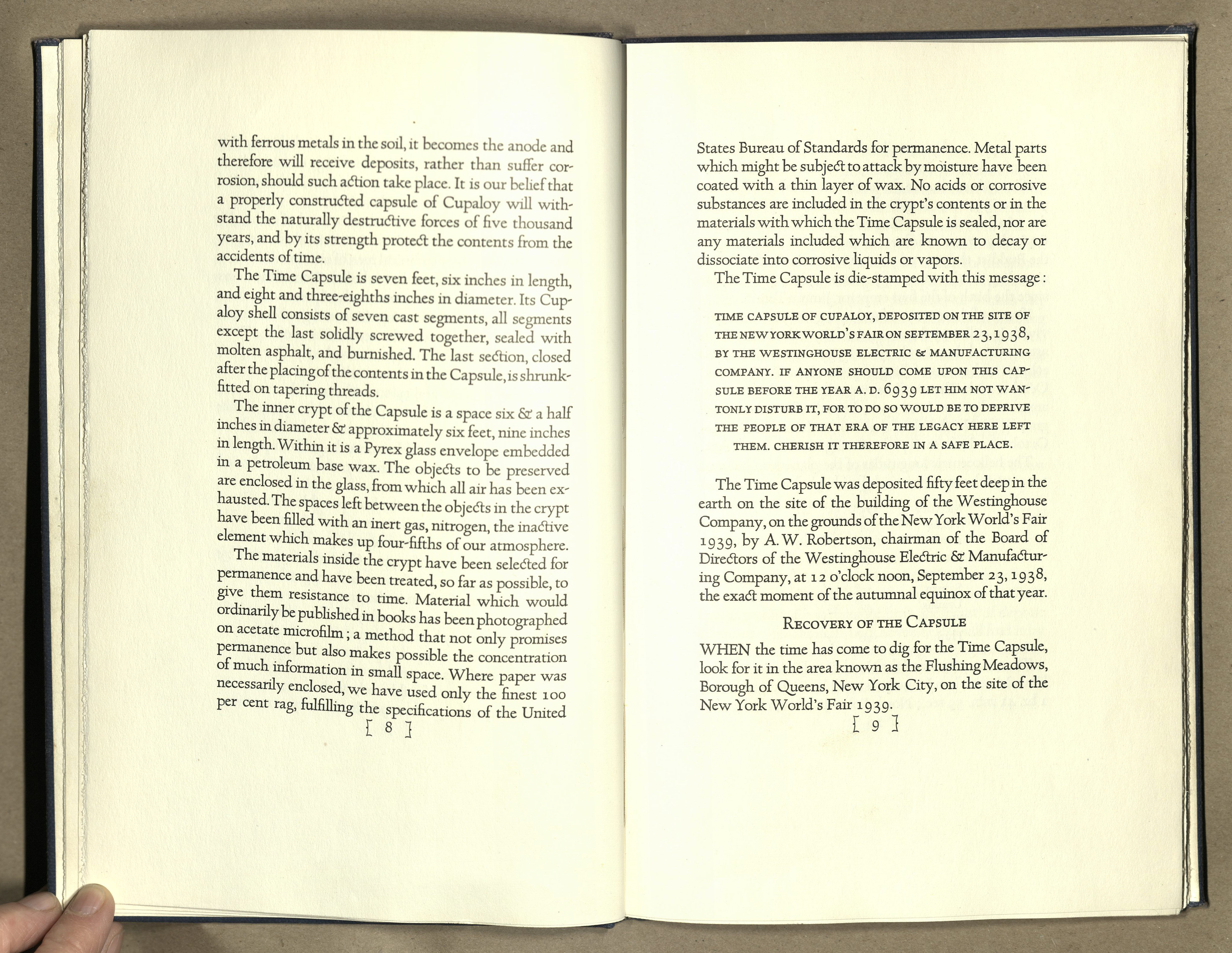

In the spirit of its theme of Progress, the Fair showcased many new materials, products, and technologies. In an effort to capture and preserve representative materials, objects, images, and texts of 1939, Westinghouse conceived of a Time Capsule (8) that would be intended to be a tangible record of our civilization to endure for 5,000 years:

The future researcher or the future archaeologist, going over the grounds of this Fair, will perchance come upon this buriend treasure of the Time Capsule and, going over the evidence, may even contradict himself and refute the adverse judgment of history that has been popularied about modern man, and come to the conclusion that as we have not been exempt from committing our own share of human follies, we have also been attentive to the things that are important and that we have done our moral duty in our own generation to affirm the continuity of human knowledge.

The sheer hubris of this endeavor becomes evident when the contents of the Time Capsule (9) reveal what a narrow scope of ‘civilization’ is actually represented, and how futile the notions of future peoples’ ability to access microfiche, newsreels, and other obsolete objects. (The only objects of with any hope of future worth (10) appear to be “a variety of seeds placed in the time capsule including wheat, corn, oats, tobacco, cotton, flax, rice, soy beans, alfalfa, sugar beets, carrots, and barley.”)

Among the 35 small, everyday items placed inside Time Capsule I were a fountain pen and an alphabet block set. Time Capsule I also contained 75 types of fabrics, metals, and plastics. Modern literature, contemporary art, and news events of the twentieth century were recorded on a microfilm "Micro-File" for placement in Time Capsule I; the "Micro-File" holds over ten million words and a thousand pictures, and has a small microscope for viewing. There are also instructions included on how to make both a large microfilm viewer and a motion picture projector for the newsreels.

Also included in the capsule were copies of Life magazine, a kewpie doll, one dollar in change, a pack of Camel cigarettes, a 15-minute RKO Pathe Pictures newsreel, a Lilly Daché hat, and millions of words of text put on microfilm rolls which included a Sears Roebuck catalog, a dictionary, and an almanac. A variety of seeds were placed in the time capsule including wheat, corn, oats, tobacco, cotton, flax, rice, soy beans, alfalfa, sugar beets, carrots, and barley.

The items in the capsule were selected to chronicle 20th-century life in the United States. During packaging of the contents, under the direction of representatives of the United States National Bureau of Standards, each object was examined to determine whether it could be expected to last 5,000 years. In addition, care was taken to select items that are not interactive and do not decompose into harmful gases or acids. Organic items (for example, seeds) were placed in sealed glass vials.

Five categories of objects were placed inside Capsule I:

- Small articles of common use

- Textiles and materials

- Essay in microfilm

- RKO newsreel

- Miscellaneous items

Every object fully labeled and described; sealed into glass; individually wrapped in heavy 100% rag ledger paper and tied with linen twine, label inside; film and microfilm inside aluminum containers lined with rag paper....

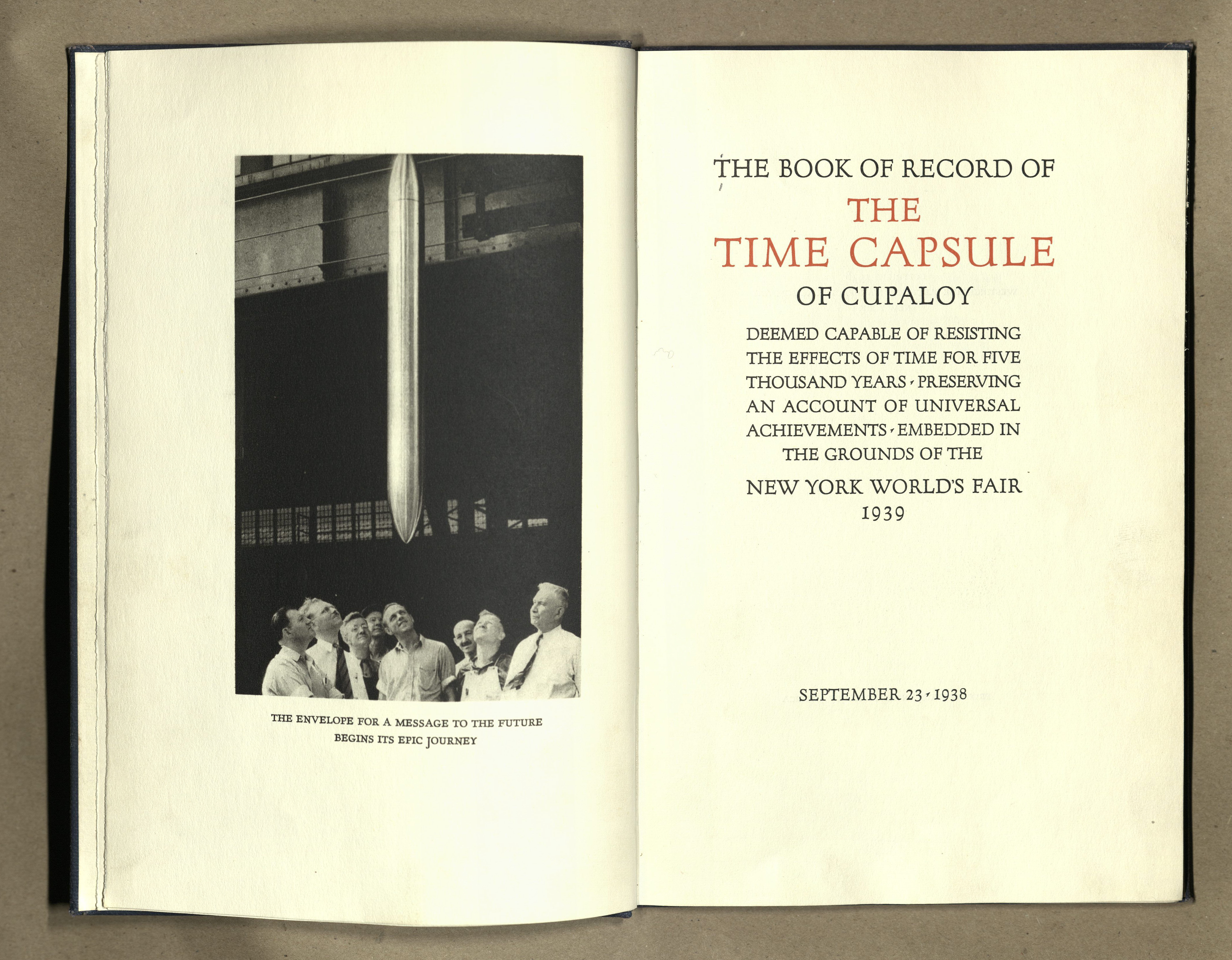

The Book of Record

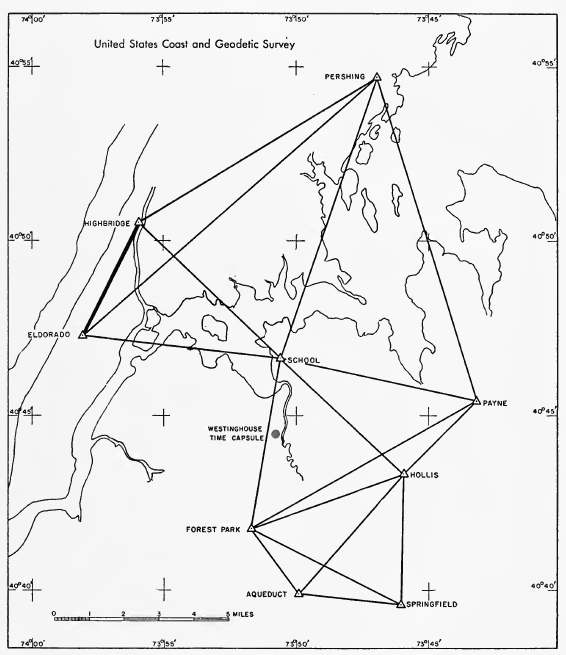

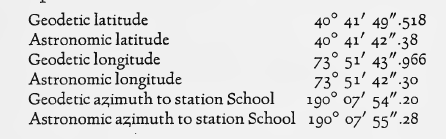

The contents of Time Capsule I were recorded in a Book of Record of the Time Capsule of Cupaloy. (11) The purpose of this book is to preserve knowledge of the existence of the time capsule for 5,000 years, and to provide assistance to the people of the year 6939 in locating and recovering it. More than 3000 copies of the book were distributed to museums, monasteries, and libraries worldwide: I stumbled across a copy in the open stacks at the John D. Rockefeller Library at Brown University and scanned it before turning it over to the John Hay Library Special Collections librarian for safekeeping. (The 1964 New York World’s Fair, (12) which was staged on the same site as the 1939 Fair, also buried a time capsule. In order to avoid confusion about the 1965 time capsule, a supplement announcing Time Capsule II was sent to the original 3,000 depositories of the 1938 edition.)

The Book of Record, designed by Frederic Goudy (view of all spreads)

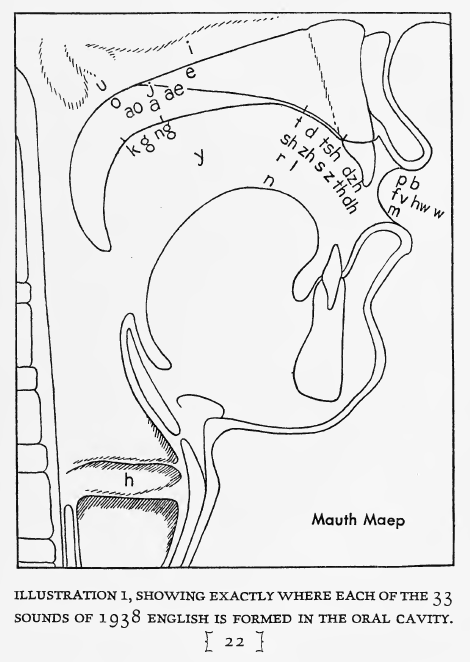

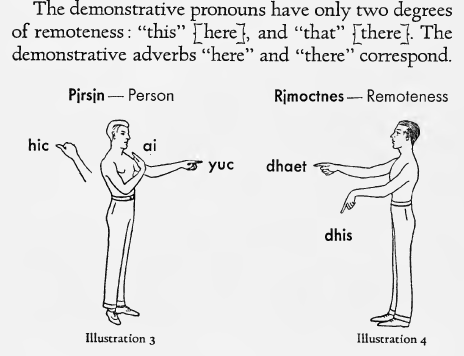

Especially absurd was the assertion that English would be the only language worth preserving, diagrammed with an elaborate phonetic system for recreating and understanding its pronunciation:

“If present-day methods of determining time are lost, future generations will be able to calculate the age of the time capsules using astronomical data. In the year 1939, there were two eclipses of the moon, falling on the third of May and the twenty-eighth of October. There were also two eclipses of the sun, an annular eclipse on the nineteenth of April, the path of annular eclipse grazing the North Pole of the earth, and a total eclipse on the twelfth of October, the total path crossing near the South Pole. The heliocentric longitudes of the planets on the first of January at zero-hours Greenwich time were as follows:...”

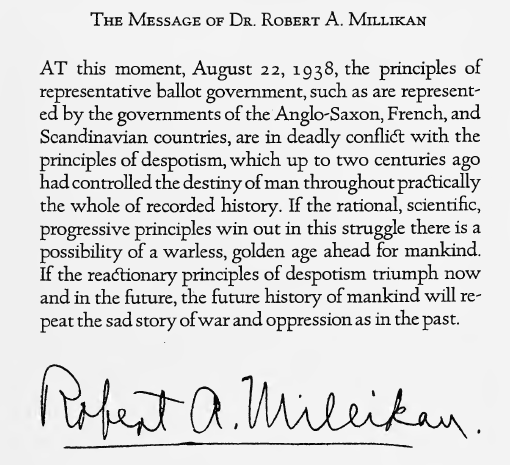

The book ends with ‘words of great men’ for future man to know us by—Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, and a particularly prescient passage from Nobel prize winning physicist, Robert Milliken:

Notes/links: (1) Soft Power: The Means to Success in Global Politics, Joseph S. Nye Jr. (Wikipedia synopsis of book); (2) Century of the Self, Part 1: The Happiness Machines, Adam Curtis; (3) The New York world’s fair, a symbol for democracy, Edward Bernays; (4) Edward Bernays (Wikipedia); (5) 1939 World’s Fair Collectibles, Ebay; (6) Monsanto’s Oddly Prescient Vision for a Plastic Future, John McDuling, Quartz; (7) 1930s: The 1939 New York World’s Fair, Barbara Kopple, Vanity Fair Decades Series; (8) The Story of the Westinghouse Time Capsule, 1939 New York World’s Fair, Prelinger Archive; (9) 1939 Westinghouse 5,000 Years Time Capsule, NY World’s Fair (YouTube); (10) Svalbard Global Seed Vault: Safeguarding Seeds for the Future, Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food; (11) The book of record of the time capsule of cupaloy, deemed capable of resisting the effects of time for five thousand years, preserving an account of universal achievements, embedded in the grounds of the New York World's fair, 1939, Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Internet Archive; (12) 1964 World’s Fair time capsule contents; (13) The Nobel Prize in Physics, 1923: Robert Milliken, nobelprize.org