1. Historical Resonance (1939–40 and 2019–20)

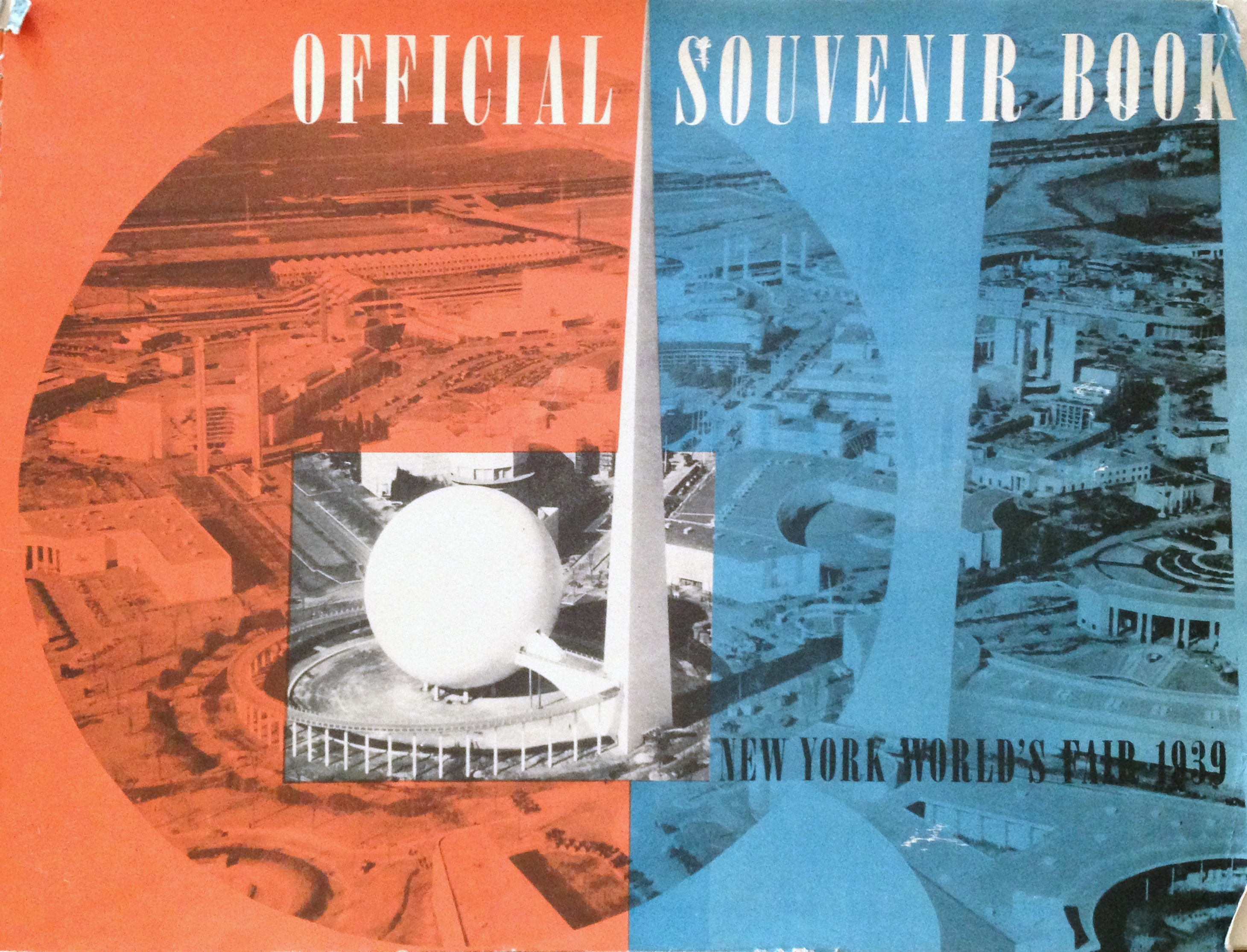

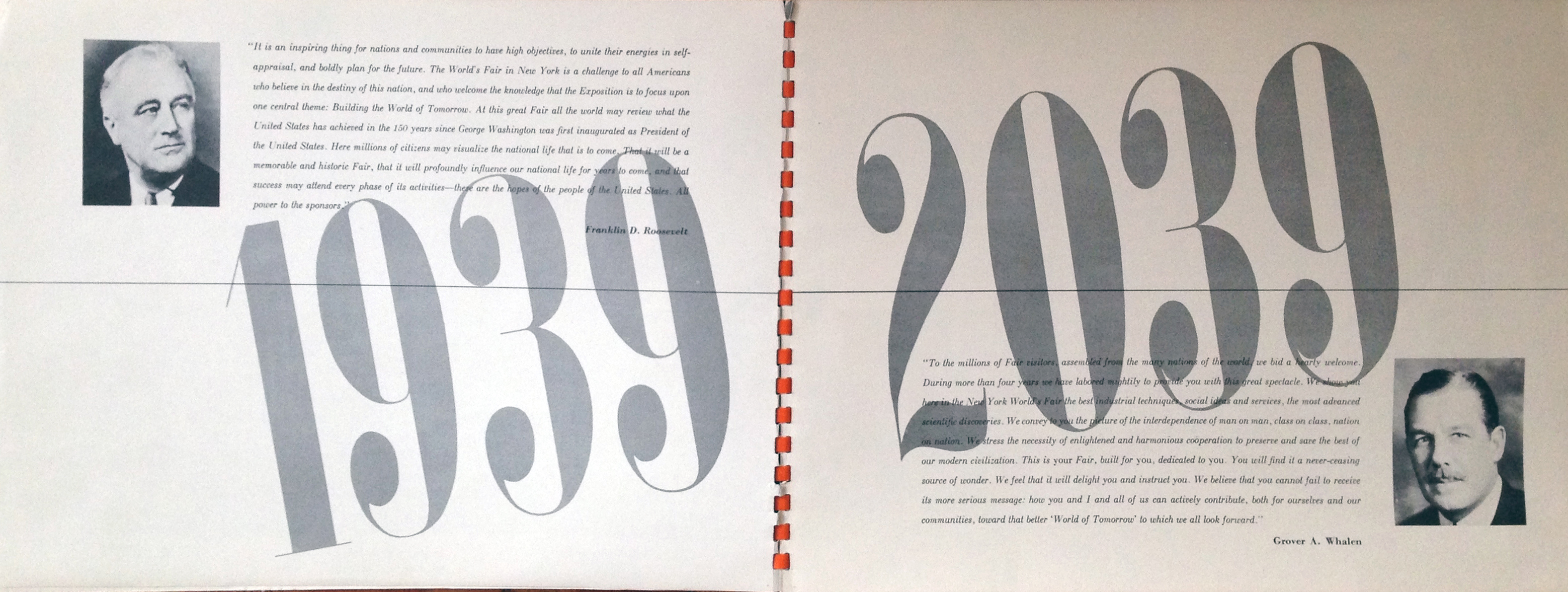

Official Guide to the Fair, outer slipcase, and cover (design attributed to Donald Deskey); introductions by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Grover Whalen, World’s Fair president and promoter:

The World’s Fair in New York is a challenge to all Americans who believe in the destiny of this nation...Here millions of citizens may visualize the national life that is to come. (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt)

During more than four years we have labored mightily to provide you with this great spectacle... We convey to you the picture of the interdependence of man on man, class on class, nation on nation. (Grover A. Whalen)

The World’s Fair in New York is a challenge to all Americans who believe in the destiny of this nation...Here millions of citizens may visualize the national life that is to come. (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt)

During more than four years we have labored mightily to provide you with this great spectacle... We convey to you the picture of the interdependence of man on man, class on class, nation on nation. (Grover A. Whalen)

There is no lack of visual and media documentation (1) of the spectacle that was the Fair. It was conceived and produced to promote optimistic visions of the future just as the Nazis invaded Poland at the advent of the outbreak of World War II. The Fair unfolded within concurrent contexts—a nation pulling itself out of the Great Depression reckoned with global conflict and the rise of nationalism and fascism, the implementation of FDR’s New Deal,(2) and efforts of early corporate public relations men (3) to author a vision of The World of Tomorrow as one of endless innovations and products for the modern citizen-consumer.

In 2019–20 we’re witnessing many parallels in global conditions (4) to the moments of portent (5) leading to the 1939–40 World’s Fair: contradictory forces for public policy and for corporate control; the testing of democratic ideals by rising nationalism, fascism, and authoritarian rule; (6, 7, 8) the endless production and flow of products to consumers from a group of corporations (9) and entities (10) holding hegemonic control over the people, places, things, and events that shape our interpretations—and experience—of current ‘civilized’ life. (In what is a largely futile effort to ‘keep up’ with the history being written today as it resonates with the history of 1939, part of this project is to assemble a growing spreadsheet (11) of texts and articles as I encounter them to attempt to track and study the then-and-now contours of democracy and progress.)

Then (1939–40)

Excerpts from On the Concept of History

—Walter Benjamin, 1940 (also referred to Theses on the Philosophy of History)

The past carries a secret index with it, by which it is referred to its resurrection. Are we not touched by the same breath of air which was among that which came before? Is there not an echo of those who have been silenced in the voices to which we lend our ears today?

Progress, as it was painted in the minds of the social democrats, was once upon a time the progress of humanity itself (not only that of its abilities and knowledges). It was, secondly, something unending (something corresponding to an endless perfectibility of humanity). It counted, thirdly, as something essentially unstoppable (as something self-activating, pursuing a straight or spiral path). Each of these predicates is controversial, and critique could be applied to each of them. This latter must, however, when push comes to shove, go behind all these predicates and direct itself at what they all have in common. The concept of the progress of the human race in history is not to be separated from the concept of its progression through a homogenous and empty time.

Historicism contents itself with establishing a causal nexus of various moments of history. But no state of affairs is, as a cause, already a historical one. It becomes this, posthumously, through eventualities which may be separated from it by millennia. The historian who starts from this, ceases to permit the consequences of eventualities to run through the fingers like the beads of a rosary. He records the constellation in which his own epoch comes into contact with that of an earlier one. He thereby establishes a concept of the present as that of the here-and-now, in which splinters of messianic time are shot through.

Excerpts from On the Concept of History

—Walter Benjamin, 1940 (also referred to Theses on the Philosophy of History)

The past carries a secret index with it, by which it is referred to its resurrection. Are we not touched by the same breath of air which was among that which came before? Is there not an echo of those who have been silenced in the voices to which we lend our ears today?

Progress, as it was painted in the minds of the social democrats, was once upon a time the progress of humanity itself (not only that of its abilities and knowledges). It was, secondly, something unending (something corresponding to an endless perfectibility of humanity). It counted, thirdly, as something essentially unstoppable (as something self-activating, pursuing a straight or spiral path). Each of these predicates is controversial, and critique could be applied to each of them. This latter must, however, when push comes to shove, go behind all these predicates and direct itself at what they all have in common. The concept of the progress of the human race in history is not to be separated from the concept of its progression through a homogenous and empty time.

Historicism contents itself with establishing a causal nexus of various moments of history. But no state of affairs is, as a cause, already a historical one. It becomes this, posthumously, through eventualities which may be separated from it by millennia. The historian who starts from this, ceases to permit the consequences of eventualities to run through the fingers like the beads of a rosary. He records the constellation in which his own epoch comes into contact with that of an earlier one. He thereby establishes a concept of the present as that of the here-and-now, in which splinters of messianic time are shot through.

Now (2019–20)

From The Speculative Time Complex, an interview between Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik

Complex societies—which means more-than-human societies at scales of sociotechnical organization that surpass phenomenological determination—are those in which the past, the present and the future enter into an economy where maybe none of these modes is primary, or where the future replaces the present as the lead structuring aspect of time. ….If we are post-contemporary, or post-postmodern, post-internet, or post-whatever — because we are now post-everything—it is because historically-given semantics don’t quite work anymore. If the speculative is a name for the relationship to the future, the “post-” is a way in which we recognize the present itself to be speculative in relationship to the past. We are in a future which has surpassed the conditions and the terms of the past.

The speculative isn’t just how the future makes the present. It’s also that the present itself is a speculative relationship to a past that we have already exceeded.

-------------

From What is at Stake in the Future?

—Alex Williams & Nick Srnicek

Every ‘future’ inscribes a demand upon the present. This is so whether at the level of human imagination, or within the sphere of political or aesthetic action necessary to reach towards their realisation. Futures make explicit the implicit contents of our own times, crystallising trajectories, tendencies, projects, theories and contingencies. Moreover, futures map the absent within the present, the presents which could never come into actuality, the wreckage of dreams past and desires vanquished. Futures are speculative, libidinal, suggestive and, perhaps, ultimately unattainable...

From The Speculative Time Complex, an interview between Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik

Complex societies—which means more-than-human societies at scales of sociotechnical organization that surpass phenomenological determination—are those in which the past, the present and the future enter into an economy where maybe none of these modes is primary, or where the future replaces the present as the lead structuring aspect of time. ….If we are post-contemporary, or post-postmodern, post-internet, or post-whatever — because we are now post-everything—it is because historically-given semantics don’t quite work anymore. If the speculative is a name for the relationship to the future, the “post-” is a way in which we recognize the present itself to be speculative in relationship to the past. We are in a future which has surpassed the conditions and the terms of the past.

The speculative isn’t just how the future makes the present. It’s also that the present itself is a speculative relationship to a past that we have already exceeded.

-------------

From What is at Stake in the Future?

—Alex Williams & Nick Srnicek

Every ‘future’ inscribes a demand upon the present. This is so whether at the level of human imagination, or within the sphere of political or aesthetic action necessary to reach towards their realisation. Futures make explicit the implicit contents of our own times, crystallising trajectories, tendencies, projects, theories and contingencies. Moreover, futures map the absent within the present, the presents which could never come into actuality, the wreckage of dreams past and desires vanquished. Futures are speculative, libidinal, suggestive and, perhaps, ultimately unattainable...

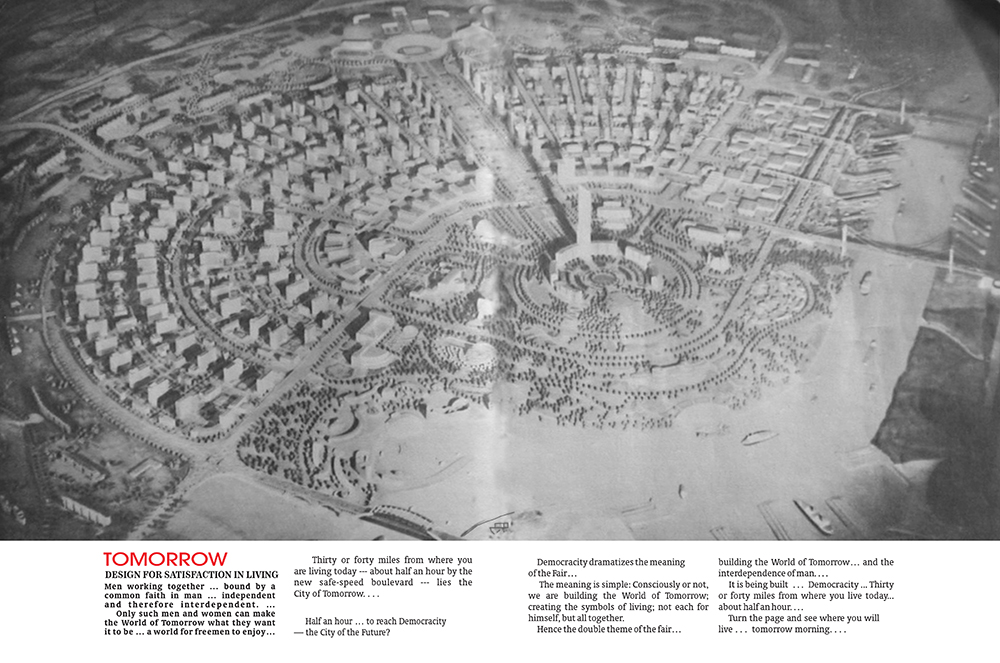

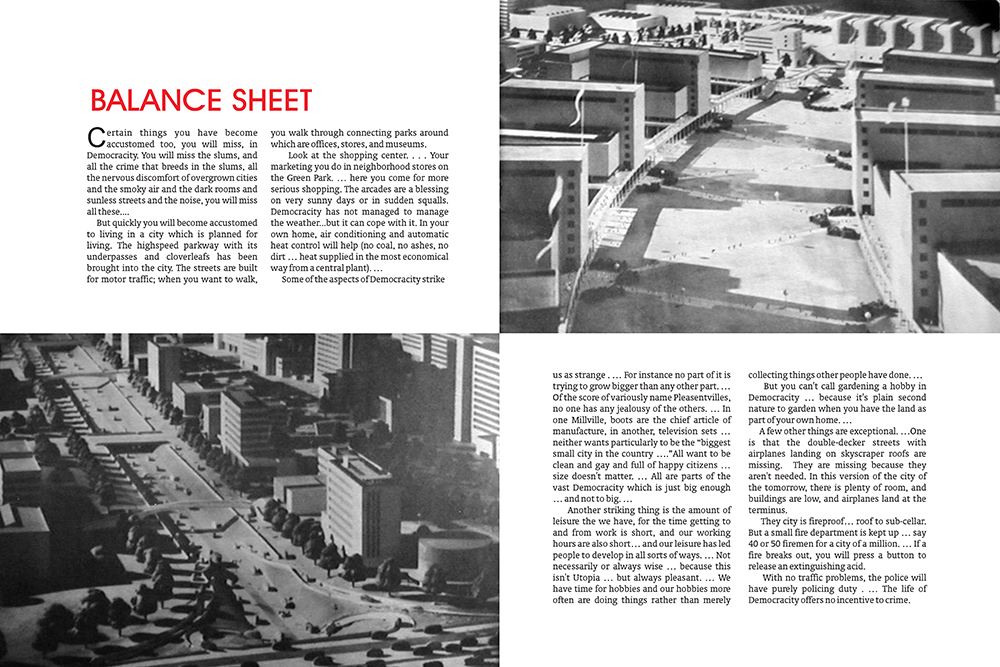

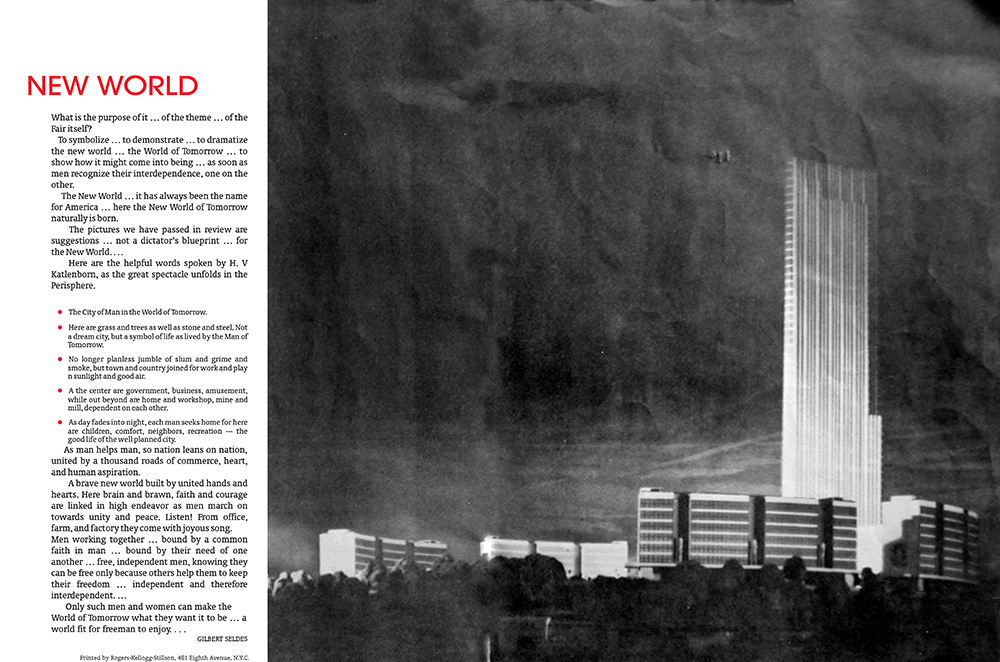

All aspects of the Fair were tasked with visualizing the themes of Democracy and Progress, a gigantic effort of public relations and design to render an optimistic future. Henry Dreyfuss’s Democracity was the 1939 World’s Fair model city for an improved World of Tomorrow, proposing centralized spatial and transportation systems for improved civic life. But in contrast to the optimistic tone of the Fair, the brochure text issues a warning that reveals how truly fragile Democracy was in 1939:

The men and women who in the towns and cities you see down there represent all Americans learning to work, to play, to struggle, to sing together. ...

But if we do not learn quickly the World of Tomorrow will not come into existence. The World of Today and Yesterday will be destroyed by men who do not believe in creative humanity—One side is the World of Tomorrow built by millions of free men and women, independent and interdependent… On the other side is chaos.’

(Above) Your World of Tomorrow brochure accompanying the Democracity exhibition designed by Henry Dreyfuss within the Fair’s signature Perisphere and Trylon theme building.

‘On The Other Side is Chaos’

The world of 1939 which the World’s Fair set out to optmistically display was at odds with actual events of global political discord unfolding in a run-up to World War II. This misalignment is especially resonant in the present moment, as the attention of the world is focused on the fate of democracy (12) itself—with daily recursions of political, economic, and social struggle that are largely ‘unfinished business’ from the past.

Today at the Fair Today excerpt, opening day April 30, 1939, Vol. 125. Today at the Fair was published daily to provide events listings and editorial content, and made scant mention of the onset of World War II with the Nazi invasion of Poland in September, 1939.

(top and right) The New York Times front page and excerpt, Monday September 4, 1939, the day war was declared: “On this—perhaps one of the most eventful and anxious days in the world’s history—the New York World’s Fair has had is day of greatest attendance.”

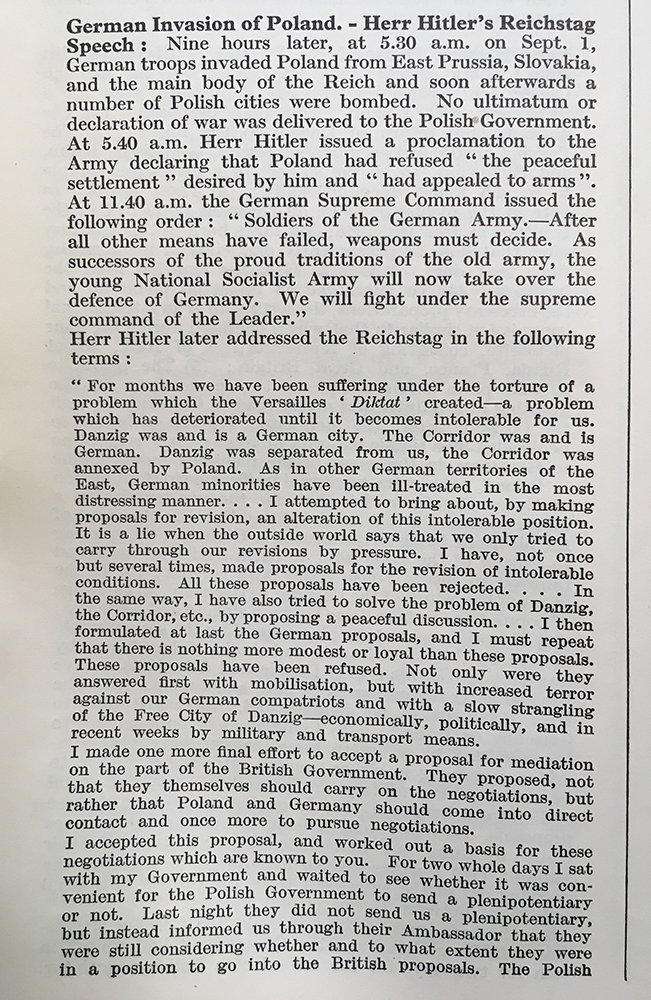

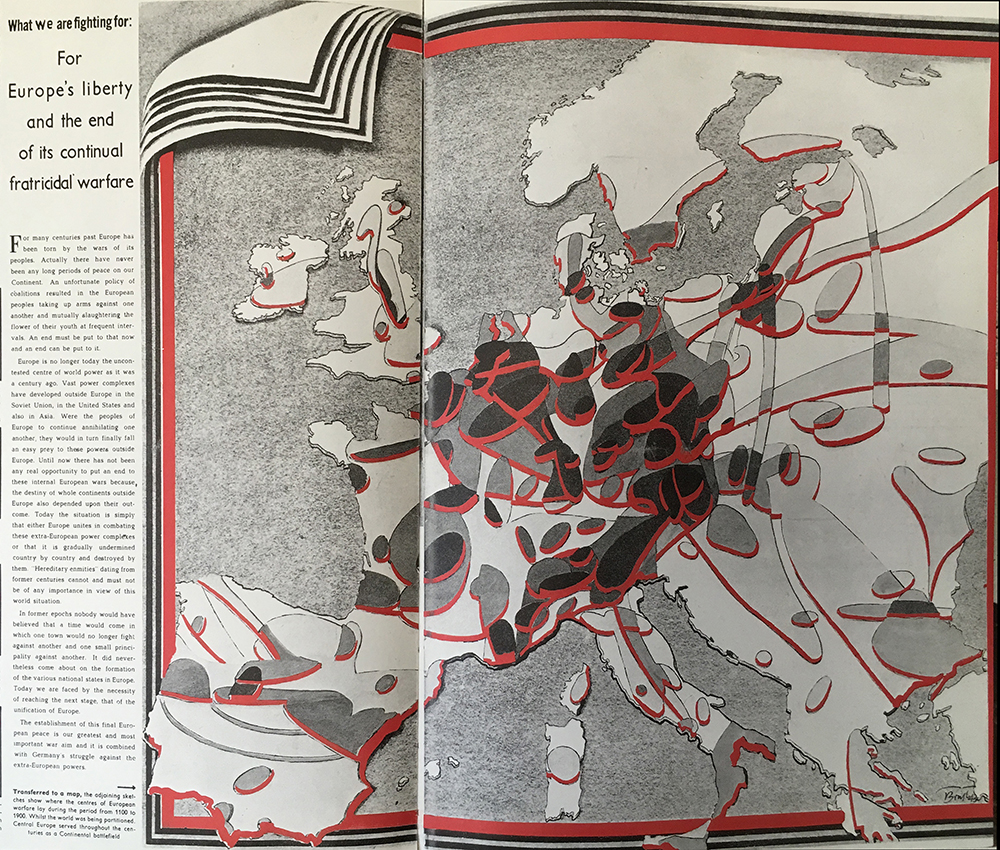

Keesing’s Contemporary Archives contains maps of war, news accounts, and key 1939 transcripts of diplomatic speeches and decrees, including Hitler’s Reichstag speech of Sept. 1, Hungary’s Anti-Jewish legislation on Dec. 27, and Roosevelt’s Defense of Democracy speech to Congress on Jan. 4.

How did visitors to the 1939 World’s Fair square its predictions for the future with the more immediate and dire future of World War? Given the current challenges to democracy—and our very human appetite for spectacle and diversion—one wonders what we may be blind to today, willfully distracted from considering what might transpire if history is indeed doomed to repeat itself. Recent publications by scholars and statespeople such as Steven Levitsky’s and Daniel Ziblatt’s How Democracies Die (13) and Madeline Albright’s Fascism: A Warning (14) are only a few of the urgent calls for consciousness as we witness signs of democratic erosion—including an unfolding presidential impeachment (15) and disinformation campaigns by foreign powers (16) as 2019 enters the election year of 2020.

The 1939–40 World’s Fair themes of Democracy and Progress still remain huge abstractions in 2019–20, with ‘progress’ largely interpreted as an economic condition that can confuse our understanding of how to measure and judge a successful democracy. In the mix of technology, goods, trade, politics and the stock market (and even within the seemingly benign aspects of the 1939–40 World’s Fair) global conflict persists at inflection points where Democracy and Progress overlap. The World’s Fair performed versions of these abstractions; the impending World War (18) would interrogate them and test their limits.

Andrea Flynn and Susan R. Homberg write in The Nation: (17)

“The conditions [in the 1930s] to which FDR was responding are not that dissimilar from those in which we currently find ourselves. Neoliberal policies have driven economic inequality to pre-Great Depression levels, with communities of color and women shouldering an outsized burden. ...The consolidation of corporate power today is at a scale we have not seen in over a century, and workers are feeling disenfanchised and powerless. ... These trends have arguably sown the seeds of fascism, which are germinating in Europe, Latin America, and even here in the United States, much as they did in Germany in the 1930s.”

(below) Details and pages from In the Shadow of Tomorrow by Dutch author J. Huizinga was published in 1936 and speculated on all that would come to pass in 1939. The book also dwells on historical resonance, with chapters such as ‘The Present Crisis Compared with Those of the Past’ and ‘New Fears and Old.’