2. Design Makes the Future Its Business

Many designers and craftspeople gave visual form to the Fair’s speculations on the future, from graphic messages to the concrete material forms of objects and architecture. During the Depression years leading up to the Fair, design projects were likely few and far between as the economy stalled after the 1929 financial crisis. In a fascinating article, When Modernism Was Still Radical: The Design Laboratory and the Cultural Politics of Depression-Era America,(1) American Studies Professor Shannan Clark writes about the short-lived Laboratory School of Industrial Design which was developed in 1935 by the Federal Art Project (FAP), one of the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) cultural programs:

As the first institution in the United States to offer comprehensive education in modernist design, its introductory brochure claimed that it had been “created to supply a hitherto unfulfilled and pressing need in America” for people with the skills to devise, package, and promote consumer products that were styled to sell, thereby stimulating economic recovery. By emphasizing “coordination in the study of esthetics, industrial products, machine fabrication and merchandising,” the school would “train designers, not specialized craftsmen, by correlating thorough instruction in the general principles of design and fine arts with shop practice.”

The school’s Director, a visionary woman named Frances Pollak,(2) oversaw all of the FAP programs in New York City, and hired an advisory board that included design luminaries, many of whom were key designers for the 1939 New York World’s Fair (Raymond Loewy, Walter Dorwin Teague, Donald Deskey, Gilbert Rhode, and others):

The prospectus for the school that Pollak prepared for Cahill reflected the thorough influence of progressive social theory, pedagogy, and design. Her comprehensive bibliography featured major texts by social theorists and scholars like John Dewey, Charles Beard, and Lewis Mumford along with writings by important modernist architects and designers such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Le Corbusier. ... From the day its doors opened, FAP administrators and consultants imagined the Design Laboratory as an integral component of their ambitious plans to democratize American culture.

The school suspended its regular operations at the end of 1939 and permanently disbanded in the spring of 1940, scattering its faculty and students throughout the design profession.

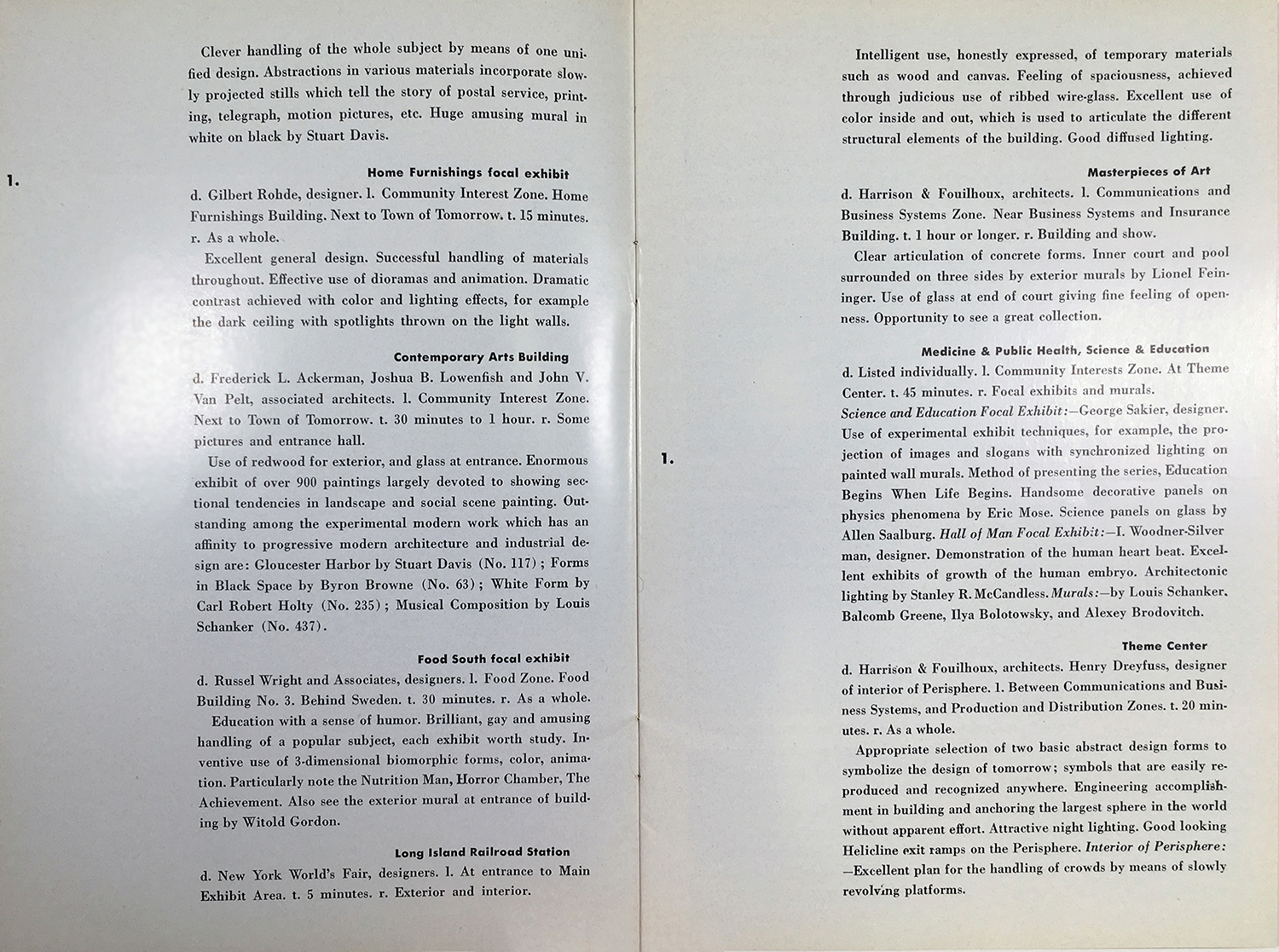

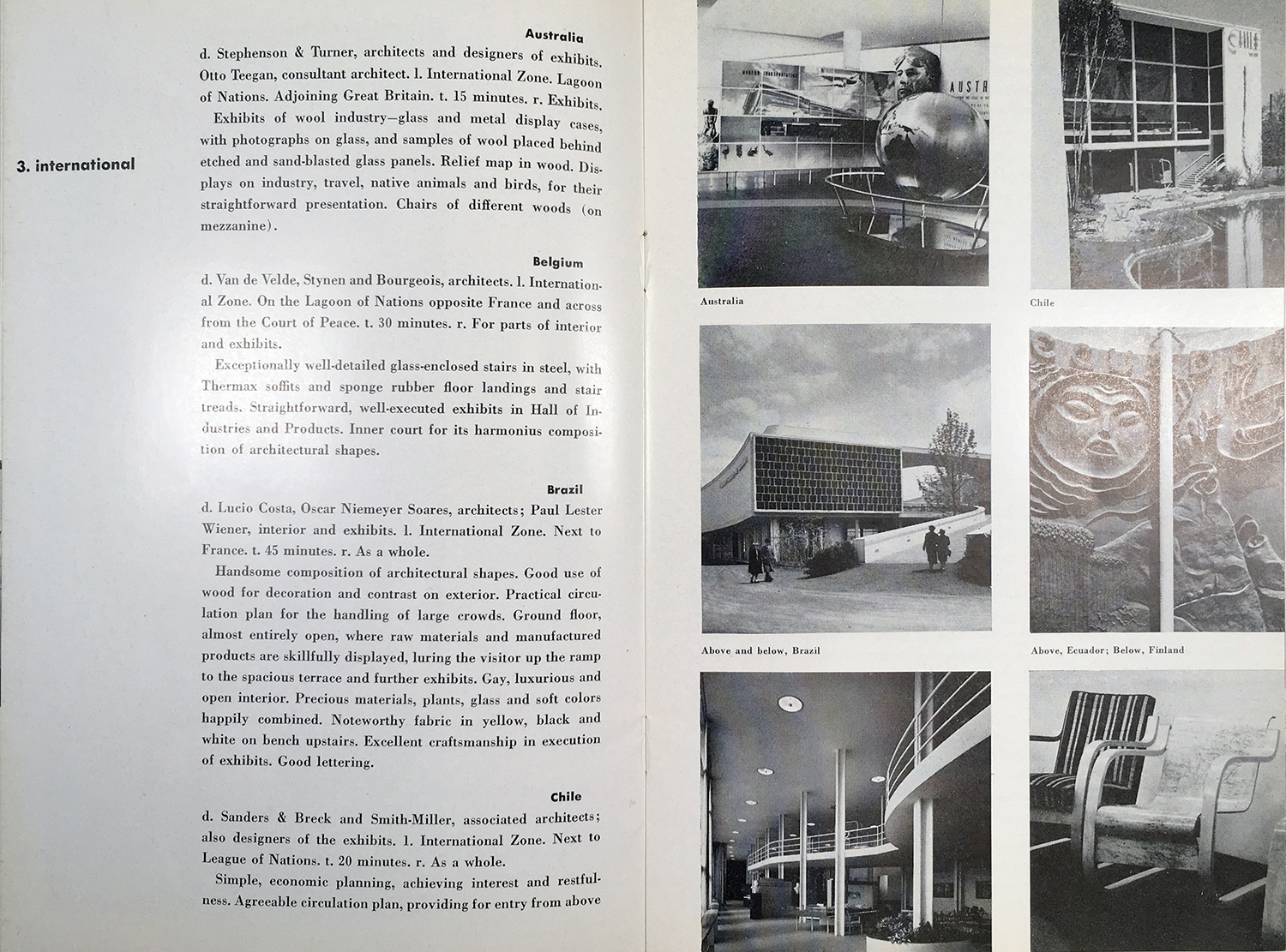

A Design Student’s Guide to the New York World’s Fair was designed by a very young Paul Rand, “a graphic arts prodigy, who joined the school [to teach] in the fall of 1938. At the age of twenty-three he had become an art director for Esquire magazine and had won critical acclaim for the covers he designed for the leftist cultural review Direction. As a faculty member, Rand supervised the compilation and publication of A Design Students’ Guide to the New York World’s Fair in 1939.”

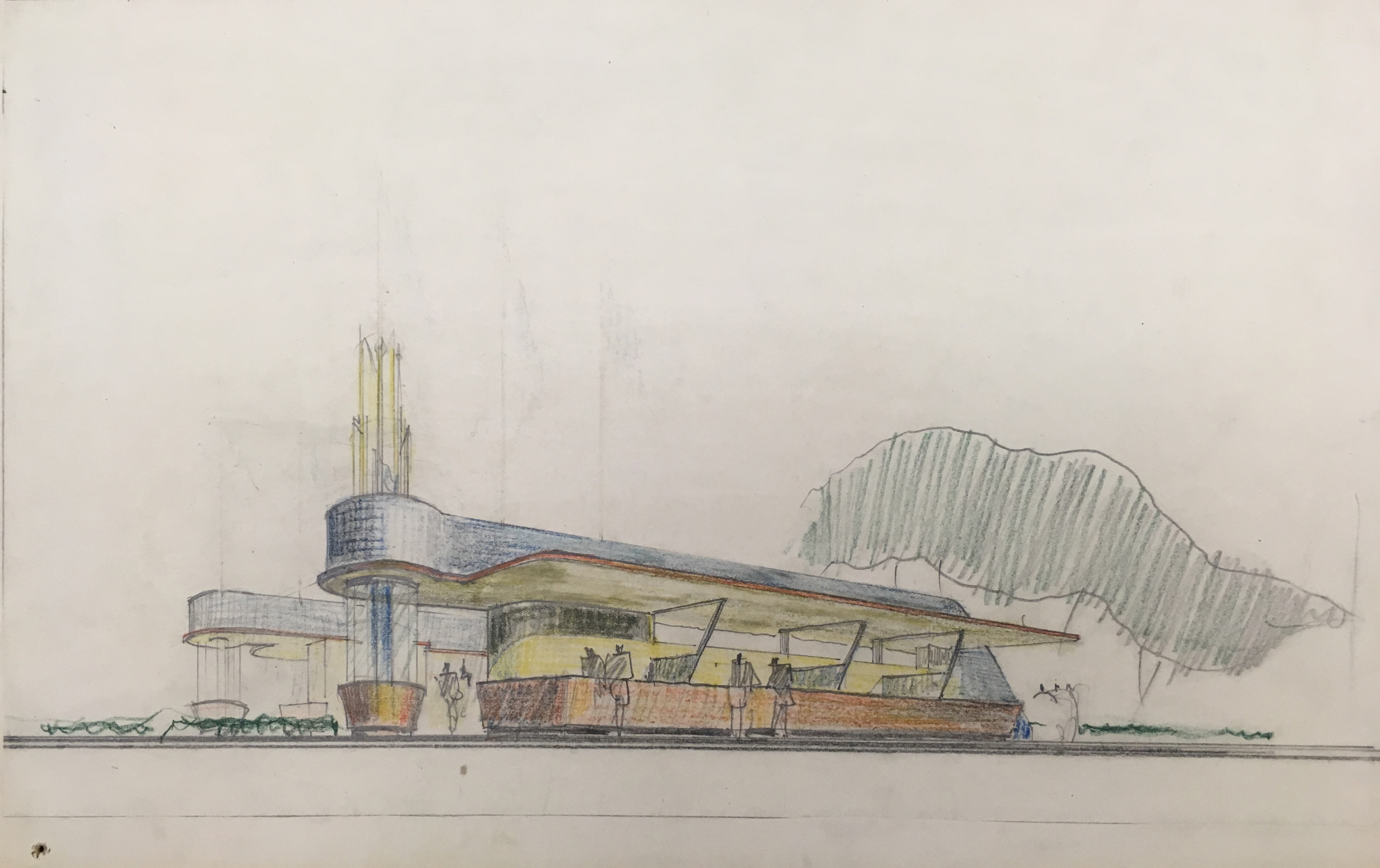

The NYPL archive holds many original renderings (by anonymous designers as well as the more famous ones) for architectural pavilions and kiosks, menus, ads, and other graphics. They characterize a modernized, streamlined, and hopeful presentation of the future: our system of living made clear to us...an understanding of what all these things mean to the aspirations and the wishes and the desires of those who view them.

The archive is full of branding material for all aspects of the fair—part Statue of Liberty seal, and part Trylon and Perisphere. Together these signature symbols brand every material piece of Fair merchandise. Design proposals and hand-rendered comps date as early as 1936 in preparation for the Fair.

(below) Some of the rougher hand-rendered sketches for the Fair’s advertisements in the logo mechanicals, lettering on board, and airbrushed images on the way to design approval.

NYPL has digitized only a minute portion of this gigantic archive, and much of this ephemera has likely not been seen or published. There are plans on paper for both the outside and inside of the Fair’s features: architectural renderings embrace streamlined aesthetics for pavilons and kiosks; an proposals for narrative theme displays. Focal Exhibit designers included Russell Wright (Food), Egmont Arens (Production and Distribution), Donald Deskey (Communications), Raymond Loewy (Transportation), and others

![]()

![]()

![]()

Prominent industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes (3) created exhibits for the Fair, most notably The Futurama large-scale layout for the city of the future within the General Motors Building.

In her compelling article The Futurama Recontextualized: Bel Geddes’s Eugenic “World of Tomorrow” (4) (heavily excerpted here), Christina Gogdell illuminates the disturbing connections between Bel Geddes’ streamlined design and eugenics ideology within design for the Fair:

The Futurama was one of four exhibits he proposed for the New York World’s Fair, two of which were never produced and have been consistently overlooked by cultural historians. Yet the narrative revealed by these four, in addition to Bel Geddes’s little probed acceptance of eugenics and belief in the fourth dimension as the evolution of consciousness, reveal the centrality of the goal of evolutionary progress to his vision of the future. Beyond offering in-depth analysis of Bel Geddes’s exhibits for the Fair, this discussion serves as a case study for ways that eugenic ideology infiltrated material culture during this era. I contend that eugenic thinking operated as a guiding framework within a certain cultural psyche without which the streamlined style in industrial and architectural design would not have resonated with such force nor have had such international appeal. Eugenicists adamantly rejected ugliness of the body as a sign of inner genetic deficiency and disease and demanded functional, hygienic, and physically fit bodies as the basis of a beautiful and healthy future race. So too did streamline industrial designers abhor the superficial ugliness, decoration and dirt-catching surfaces of predesign-era products that seemingly masked inner corruption and functional impotence and contributed to an unsanitary germ-rich environment. Through their efforts which paralleled the goals of early eugenicists, designers began reshaping products from the inside out, creating at least in rhetoric functional forms with fit exteriors which honestly revealed the inner wholesomeness of the product.

... Both eugenics and streamlining in the U.S. were financially supported and promoted largely by Anglo-Saxon corporate capitalists and middle- to upper-middle-class educated citizens as top-down reform programs. As William Pretzer points out, despite the widespread distribution and reasonable prices of many streamlined products, the style was “hardly egalitarian or democratic” in either its intent or advertisements. Both eugenics and product advertising drew upon and furthered “human engineering”; research in both genetic and psycho-logical/behavioral manipulation was funded by corporate research foundations. The corporate backing of both the eugenics movement and the New York World’s Fair, the Fair’s emphasis upon the marriage of science and technology with the expected progeny of a future utopia, and its pinnacle role in celebrating the streamlined style all combine to open the four exhibits that Bel Geddes proposed for the Fair (as well as his personal beliefs) to an examination revealing the imprint of evolutionary and eugenic ideology on the products of material culture.

—From The Futurama Recontextualized: Norman Bel Geddes’s Eugenic “World of Tomorrow” by Christina Cogdell, American Quarterly, Vol. 52, Number 2, June 2000, pp. 193–245

—From The Futurama Recontextualized: Norman Bel Geddes’s Eugenic “World of Tomorrow” by Christina Cogdell, American Quarterly, Vol. 52, Number 2, June 2000, pp. 193–245

Egmont Arens, the ‘Father of Planned Obsolescence’

Bel Geddes’ connections to eugenics cast him as one character occupying the shadows within the bright spectacle of the Fair. Edward Bernays, the ‘father of public relations,’ and Egmont Arens, ‘the father of planned obsolescence,’ are the two other prominent characters that emerge from the archive as major influences to the Fair’s design concepts.

Photocollage and hand-painted comp for the Production and Distribution focal theme exhibit by designer Egmont Arens

Egmont Arens,(5) whose illustrated comps for Fair exhibits stand out in the NYPL archive, was a multi-faceted industrial designer who specialized in product design, packaging, and marketing, and is recognized as the father of planned obsolescence (6)—matching perfectly with Bernays’ appeals to the desires of the American citizen, satisfying their wants beyond merely providing for their needs. With the persuasive tactics of both Bernays’ public relations and Arens’ product design, display, and distribution, the groundwork was established for corporate branding and accelerated consumer consumption.

Their ideas for the future, more than almost any others, have haunted the present and contributed to entwined wicked problems of today—at the base level, endless consumption and waste,(7) extraction of fossil fuels and the depletion of habitat, competition for resources giving rise to xenophobia and nationalist fervor, the sobering science of irreversible climate change, and more.

The Fair offered hyperbolic visible proof of abundance and supply, insisting upon a vision of plenty as the outlook for The World of Tomorrow. Spectacles of display and pageantry were designed to capture and persuade the audience as the first steps of ‘consumer engineering’— so familiar to us now, but daringly optimistic at the time of the Great Depression. (below: a Ford exhibit display; Henry Ford publicity photo.)

With Roy Sheldon, Arens co-authored the book, Consumer Engineering: A New Technique for Prosperity, published in 1932: (From Wikipedia)

In Consumer Engineering, Sheldon and Arens wrote that business must accept the “world as it is,” and then to see not threats but opportunities. In fact, there was a “new world” to be charted and explored. In the first years of the Great Depression, this view was intentionally upbeat. Problems could be turned to advantage; overproduction and under-consumption could be solved by knowing the needs and wishes of consumers, by good design and use of color, by predicting fashion, not fads, and by what is now known as “planned obsolescence.”

They wrote: “Would any change in the goods or the habits of the people speed up their consumption? Can they be displaced by newer models? Can artificial obsolescence be created?”

The paragraph ends with a prescient mission statement:

“Consumer engineering does not end until we can consume

all we can make.”

Notes/links:

(1) When Modernism Was Still Radical: The Design Laboratory and the Cultural Politics of

Depression-Era America, Shannan Clark; (2) Frances Pollack, profiled within an MA thesis by Mandy Lynn Drumming (2011), Marxism, Abstraction, Ideology, and Vhutemas: The Design Laboratory Reassessed, 1935–40; (3) “I Have Seen the Future:” Norman Bel Geddes and the General Motors Futurama, Museum of the City of New York blog “New York Stories”; (4) The Futurama Recontextualized: Norman Bel Geddes’s Eugenic “World of Tomorrow”, Christina Cogdell; (5) Egmont Arens, known as ‘the father of planned obsolescence [Wikipedia]; (6) What is Planned Obsolescence, Will Kenton (the design of limited lifespan into the product to ensure consumer replacement); (7) Where Does Your Plastic Go? Global Investigation Reveals America’s Dirty Secret, multiple authors, The Guardian