2. Thematic Structures

This research project draws on mapping the fair in multiple ways, using the Fair’s ideological outline, its site layout, and its archive of graphic and textual ephemera. Together these forms suggest an associative network of graphic artifacts, architectural forms, objects, events, places, realms, and theories. Cultural, political, corporate, and design legacies from 1939 resonate with the present to provoke questions on their implications for our ‘world of tomorrow.’ The 1939–40 World’s Fair themes of Democracy and Progress were two giant abstractions that branched into constituent parts, mixing civics and business into thematic zones for exhibition and visual display—as stated by public relations man Edward Bernays,(1) ‘to sell America to the Americans.’ The archive holds many texts describing the purpose and theme of the Fair, produced ahead of time to fuse together Democracy and Progress as interdependent ideals guiding the whole enterprise, and to ensure industry involvement in the Fair.

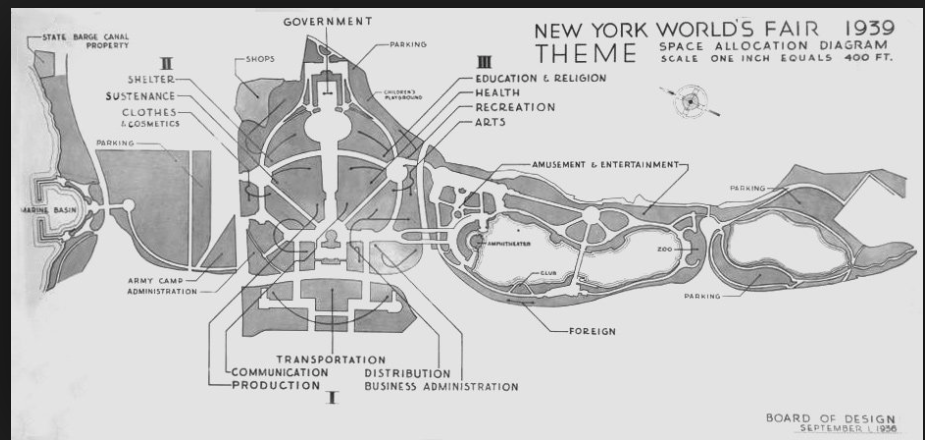

The World’s Fair theme diagram is itself a kind of readymade relational database. Its central axis places government at the top, with branching aspects meant to encompass all aspects of civic life. This diagram is an index of themes and categories, a useful key to help connect historical parallels using the Fair’s themes as nodes.

The Fair’s branching Theme Diagram also maps directly to the physical site plan, with pathways to thematic zones and pavilions. Using the diagram’s relationship to space and built structure in a database narrative, one can think of ‘the pavilion’ as a metaphor for a kind of temporal information architecture; material from past and present can come together as themes and variations that build mutable structures, allowing for recombination and disintegration over time.

(above) The New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives Division holds the New York World’s Fair 1939–40 records, including promotional texts and the Theme diagram which reflect the dual purposes of the Fair: to promote democracy, and to showcase progress through industry innovation. The theme is at the center of the radial diagram, with ‘Government’ at the top of the central axis of the Fairgrounds site. An aerial view maps the radial theme diagram directly to its physical corollary: the Fair’s site footprint.

The outline of the proposed theme for the New York World’s Fair breaks into three main categories: Goods, Comfort, and Welfare. The diagram shows Government at the top, and Amusement and Entertainment at the bottom, with Fine Art activies, Publications distribution, and Organizations’ exhibitions as programming throughout.

Each of these three main themes then branch into ever more detailed categories involving mechanics, means, elements, and particulars: materials, specialized industries, and institutions.

The 1939–40 World’s Fair had seven organizational nodes that suggest structures that can link non-linearly, mixing past and present. According to the Official Guidebook, the Fair’s seven zones were Amusement; Communications; Community Interests; Food; Government; Production and Distribution; and Science and Education.

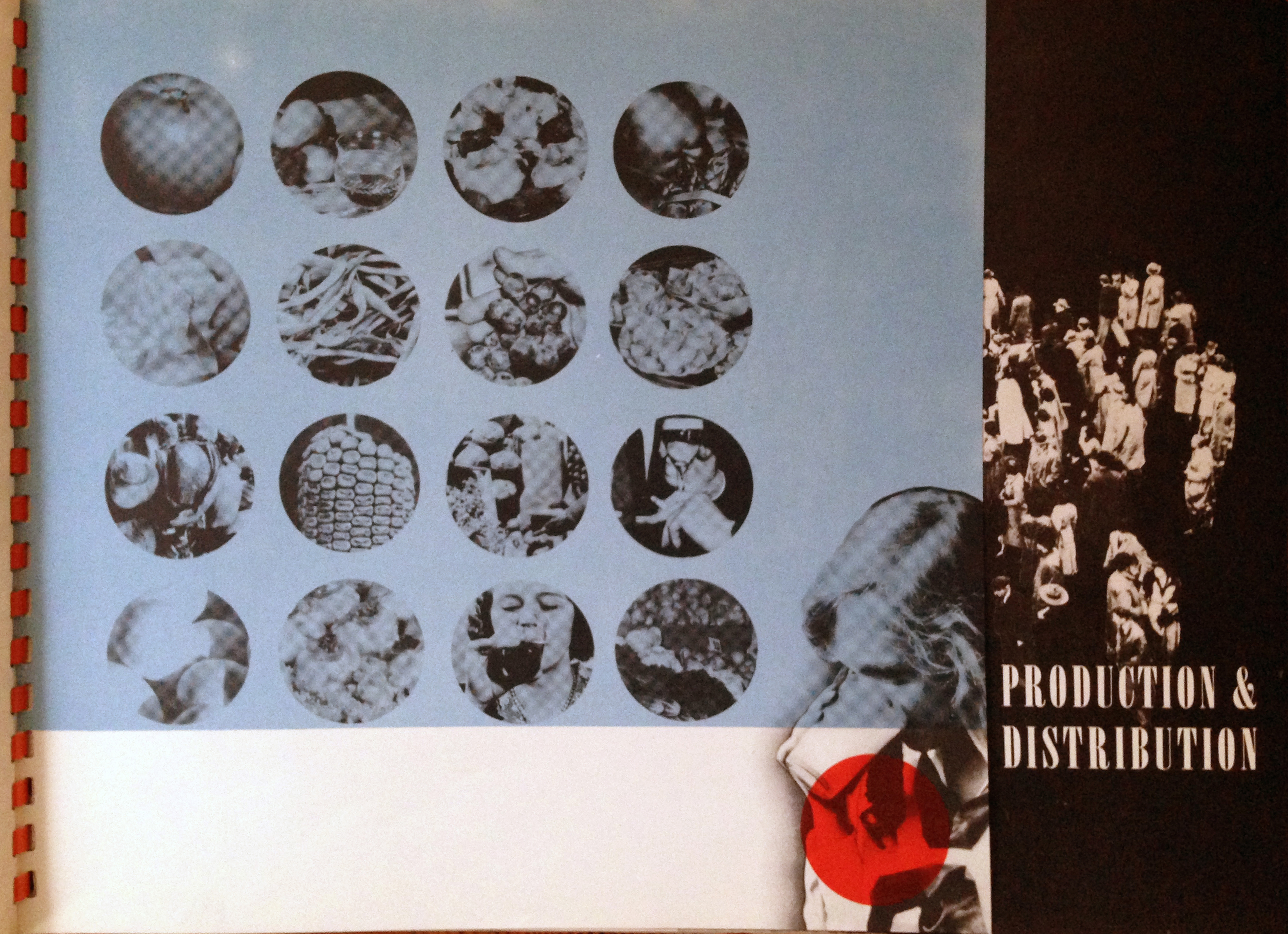

(above) Divider pages from the Official Guide to the Fair.

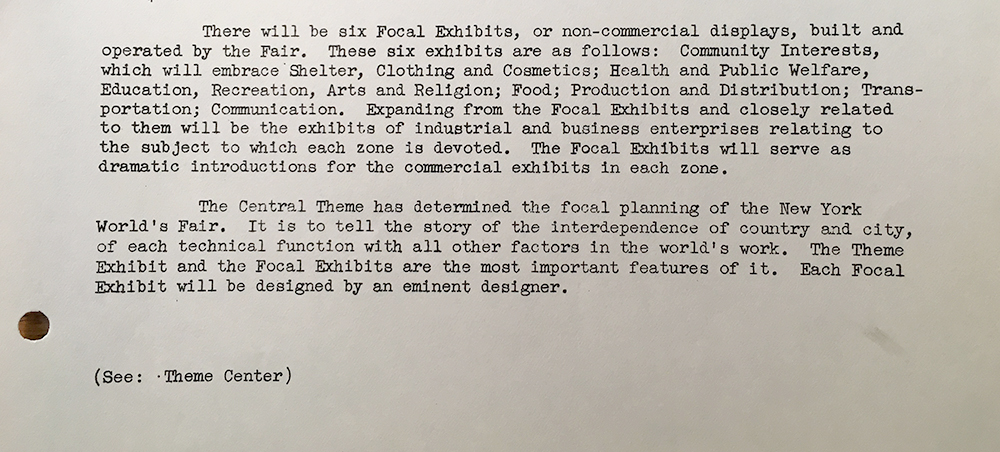

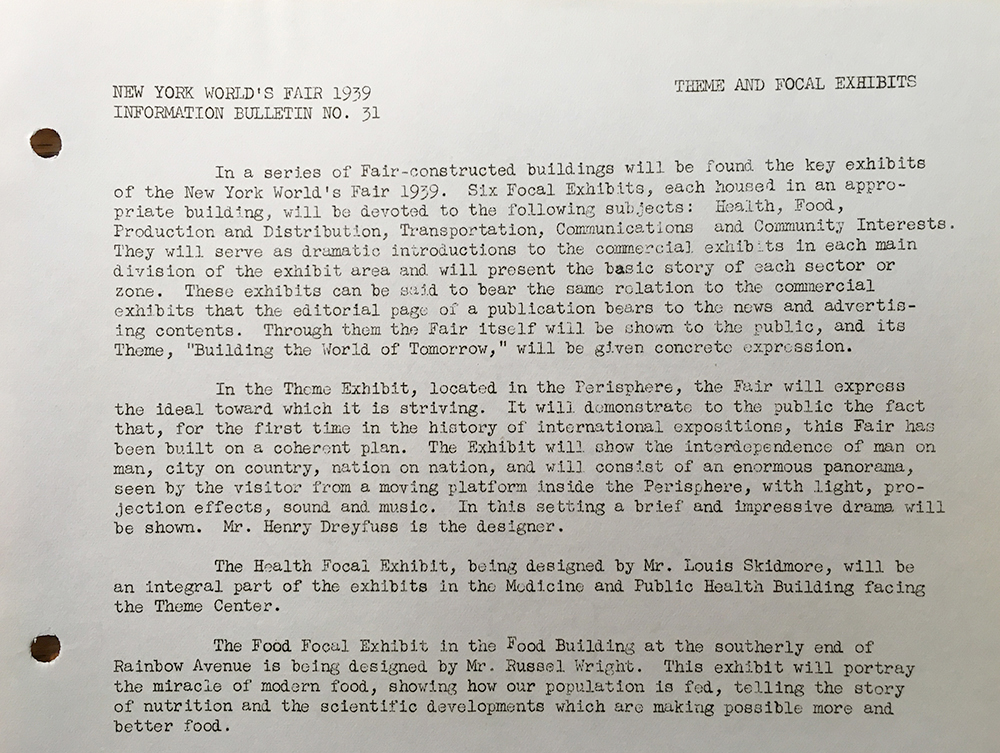

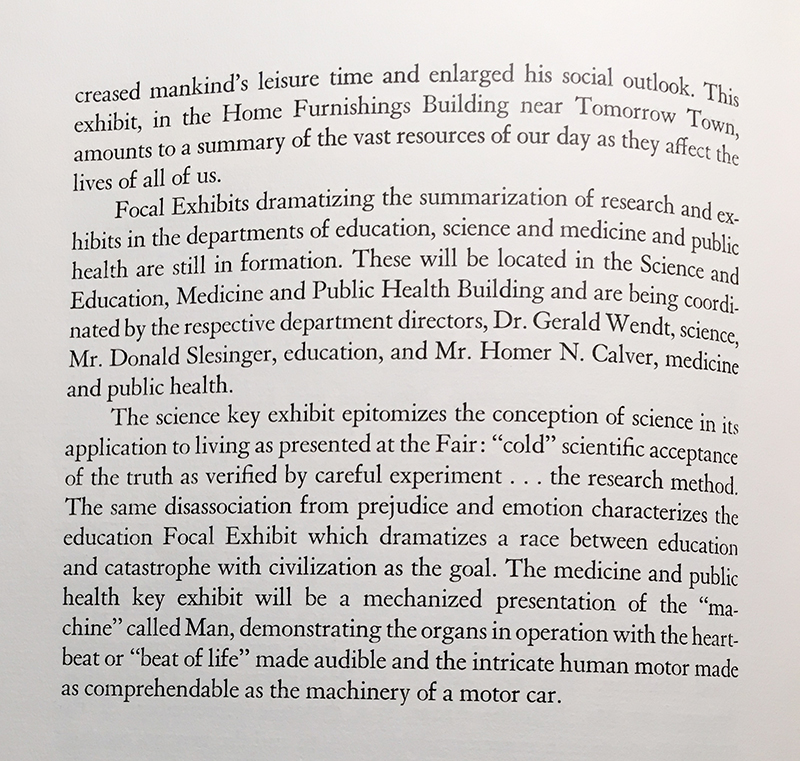

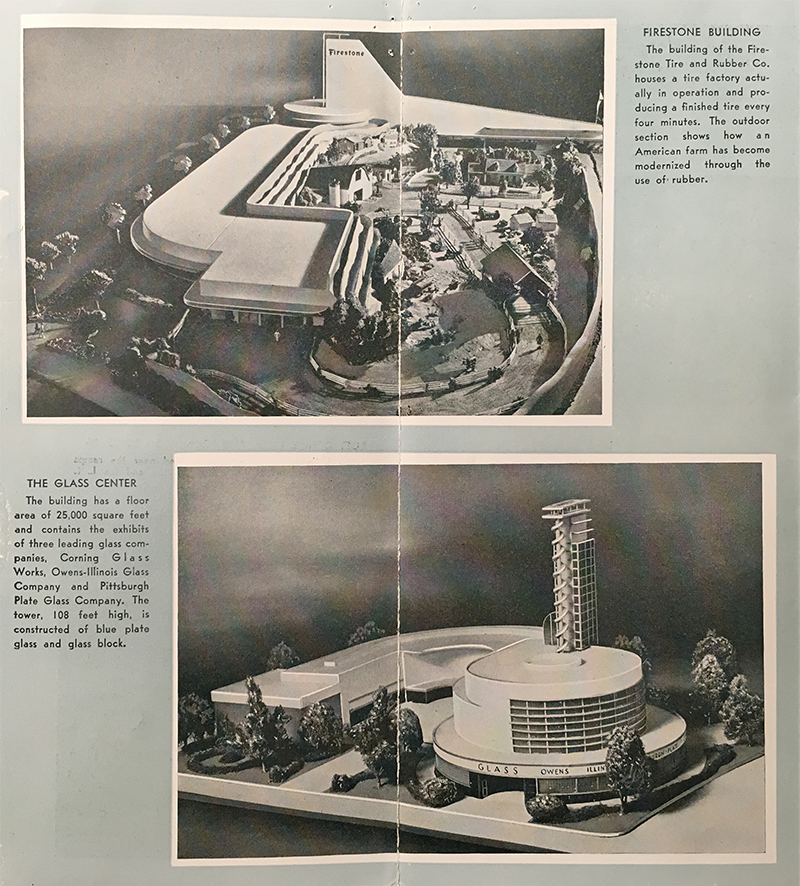

(above) The World’s Fair Information Bulletin, No. 1 describes the importance of designing thematic focal exhibits. (below) Renderings of Fair buildings and pavilions from The World of Tomorrow in Pictures multi-paneled brochure, one of the many pieces of printed ephemera produced by the Fair’s Publicity Department.

Just as the Fair’s theme diagram maps to its physical campus, the Fair Records (2) now archived at the New York Public Library are a textual map to the operational apparatus of the Fair. The centralized World’s Fair records system developed by Remington-Rand Corporation, also exhibitors at the Fair, was carefully maintained by office manager Katherine Brougher Gray (3) before being handed off to the library:

...If the “self-indexing” system designed by Remington Rand for the World’s Fair was too mechanical, Katherine Brougher Gray’s revision sought to restore an element of human logic. Her method, drawing inspiration from both naval and library filing systems, reflected the Fair as a logistical, government-industrial, diplomatic, and pedagogical endeavor. The five divisions (again: Administration, Construction, Maintenance, Participation, Public Relations) attest to the way the administrators thought of the World’s Fair, as both event and place: a place built tabula rasa and maintained for its two-year existence, then dismantled; a destination that relied on a positive image in order to draw participating “residents” (government, corporate, and organizational exhibitors; vendors; performers; amusement operators) and daily visitors; and an enterprise that required a large administrative apparatus to make it all work. The files’ organizational structure reflected the Fair’s hybrid identity. It was both a functioning city and a commercial showroom. It was a public service—intended to educate the global public about technology and democracy, to promote diplomacy, to stimulate the economy—and also a business.

...Nearly a century after that first Fair in Flushing Meadows we’re still dreaming the same dream—one of efficiency and automation and scientism, incorporated in our cities, executed in our wars, crystallized in our data, enclosed and embodied in our files.

—From Shannon Mattern, “Indexing the World of Tomorrow,” Places Journal, February 2016

Notes/links: (1) For more on Edward Bernays, ‘the father of public relations,’ see Part 3.1, Soft Power and Spectacle; (2) The New York World's Fair 1939 and 1949 Incorporated Records (pdf), NYPL; (3) The Records of the Fair Itself, Thomas G. Lannon, NYPL

From the complete records of 1939–40 NY World’s Fair at NYPL: In addition to offering an exhaustive record of the Fair Corporation, the collection serves as a remarkable compendium of the times, offering entrée to almost every facet of American life, and supporting research on any number of subjects including: the birth of the consumer society and corporatism; the rise of the automobile culture; technology’s transformation of the American home; the emergence of public relations as a profession and social force; the legacy of the New Deal; the influence of industrial design on everyday objects; urban and regional planning in 20th century America; the transformation of New York City instigated by Robert Moses from the 1930s forward; representations of race in popular culture; tensions between nationalism and internationalism in the United States; foreign participation and geopolitics; the history of burlesque and other popular entertainments; the evolution of museum didactics and display techniques; the introduction of foreign cuisines to the American public; labor relations and the rising sway of unions; the advent of mass travel and the tourism industry; and the history of other fairs and international expositions, most notably Chicago’s Century of Progress, which served in many ways as a model for the New York fair. The successful mounting of the Fair required the involvement of thousands of individuals both prominent and obscure—from incorporators and planners to stenographers and stuntmen. Consequently, the records are an ideal source for biographers and genealogists. While the collection in no small measure reveals the aspirations of the political, cultural, business, and civic leaders that financed, planned and built the Fair, the extensive correspondence from members of the public poignantly captures the anxieties of a nation still gripped by the Depression and poised on the brink of war. (nypl.org, from New York World’s Fair 1939 and 1940 Incorporated Records Scope and Content note